It’s late August, before a holiday weekend. You don’t need yet another analysis of POTUS’ attempt to fire Lisa Cook – there have been plenty already.

Instead, let’s get philosophical and consider a different question: Why Aren’t Markets Freaking Out? Paul Krugman raised that question today, and while I don’t disagree with his view, my framing is very different.

Let’s start with Benjamin Graham’s famous aphorism that “In the short run, the market is a voting machine, but in the long run, it is a weighing machine.” I would annotate1 Graham’s aphorism:

Markets are probability machines.

Sure, people “vote” with their dollars, but that’s a tautology, a definition that lacks useful context for understanding the present.

I have found that a more useful framework applies three factors:

1. The future is inherently unknown (“Nobody knows anything”)

2. Investors express their expectations via their capital

3. Market consensus is formed collectively via these flows.

Let’s flesh this out a little more:

When I say Nobody knows anything, I mean that none of us know with any certainty how any current issue will resolve. Cook’s (alleged) firing, tariffs, inflation, corporate earnings, whatever. We can analyze, estimate, extrapolate, and hypothesize, but we simply don’t know the outcome – yet.

But we can and do express our individual views by allocating capital. We form a perspective, imagine a future outcome, and identify relative asymmetries. We make a risk/reward analysis and then put cash to work. The votes Graham was referring to were those dollar investments. This is collectively the market consensus. Sometimes it’s right – all-time highs keep going higher! And sometimes it’s wrong – Lower yields! Recession! Fed cuts! But each issue reflects the collective probabilities of what might happen.

~~~

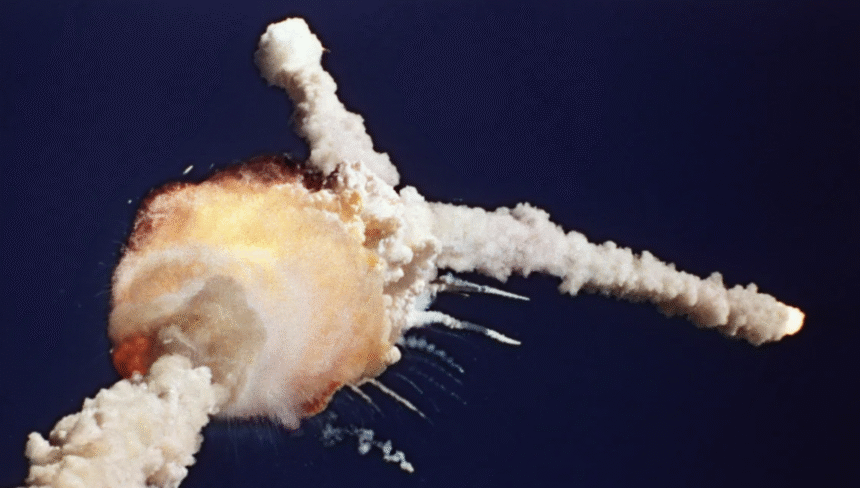

Have a read of this excerpt from James Surowiecki’s “The Wisdom of Crowds.” It discusses the January 28, 1986, space shuttle Challenger disaster:

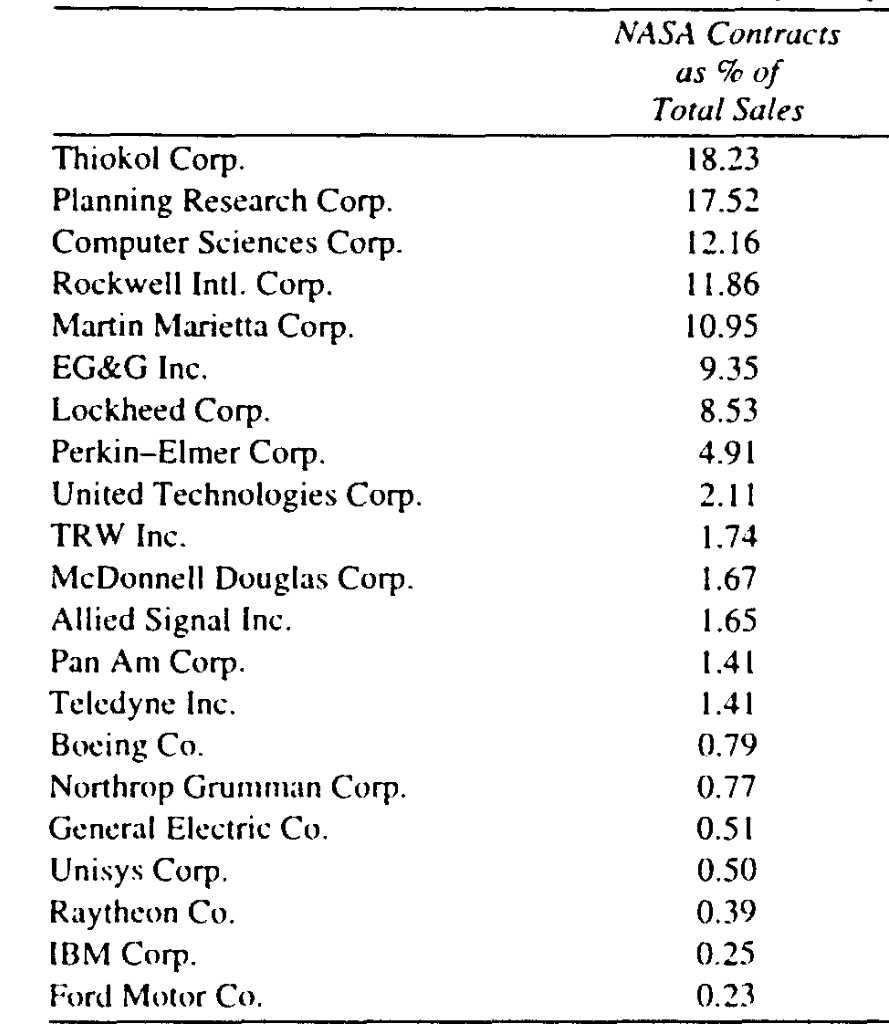

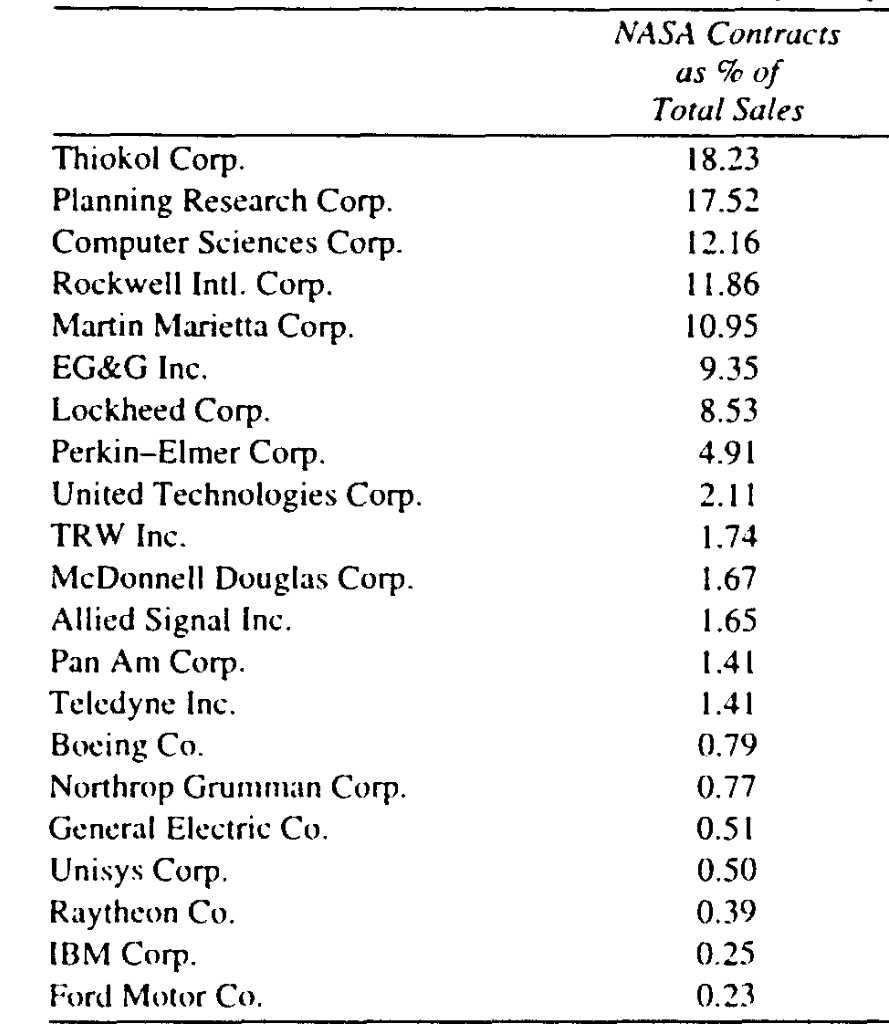

“Within minutes, investors started dumping the stocks of the four major contractors who had participated in the Challenger launch: Rockwell International, which built the shuttle and its main engines; Lockheed, which managed ground support; Martin Marietta, which manufactured the ship’s external fuel tank; and Morton Thiokol, which built the solid-fuel booster rocket.”

At the end of the day, the first three stocks were off only 3%, but Morton Thiokol’s stock closed down 12%. Many people have read into this a “Wisdom of Crowds’ interpretation” that the market figured out it was Morton Thiokol’s O-Rings to blame for the explosion.

I beg to differ.

The market did not and could not “know” that. Rather, investors made a probabilistic assessment as to what would occur to each of those four companys’ profits and stock prices if each were the one at fault. This was a probabilistic assessment of the impact on each company.

Rockwell ($8B market cap) had US aerospace, automotive, and industrial technology businesses; Lockheed ($2.5B) was an enormous defense contractor; Martin Marietta ($3B) held aerospace, defense, electronics, technology, aluminum, construction materials, and chemicals businesses. (Lockheed and Martin Marietta merged in 1995 to form the world’s largest defense contractor).

Rockwell ($8B market cap) had US aerospace, automotive, and industrial technology businesses; Lockheed ($2.5B) was an enormous defense contractor; Martin Marietta ($3B) held aerospace, defense, electronics, technology, aluminum, construction materials, and chemicals businesses. (Lockheed and Martin Marietta merged in 1995 to form the world’s largest defense contractor).

The smallest and least diversified entity was Morton Thiokol ($1.7B). It held Morton Salt, other chemical makers, and built rockets. They had the greatest exposure to the aerospace industry. NASA contracts as a percentage of Thiokol’s sales were over 18%; Rockwell was less than 12%; Martin Marietta less than 11%; Lockheed 8.5%. If any of these four companies would have been found to be a fault, it would have been most impactful to Morton Thiokol. They were, as the New York Times reported, the company with “the most to lose in terms of profits” due to the disaster.

That probability is what the markets had determined – not who was at fault.

~~~

Why are markets not freaking out? Because the highest probability case (for now) is that profits and revenues are high, the economy has remained robust, a Fed cut is forthcoming, and all of this noisy political stuff will ultimately work out in the end.

You can criticize market probabilities as a mash-up of wishful thinking and intelligent analysis. There are times, with the benefit of hindsight, that what looked like market madness was actually rational – if only we knew then what we know now. Hence, the probability machine is laying out various possible outcomes, along with prices that more or less reflect those outcomes accordingly.

The dispersion of outcomes includes a full range of possibilities. Sometimes, these are very different, even opposite, contradictory outcomes. There are times when markets appear to be failing to recognize specific risks. No doubt, there have been times when that was true. But we also need to accept that at other times, markets simply do not know.

Making probabilistic bets on very specific occasions involving people, policy, and politics is “squishy.” There is also a huge difference between assessing the likelihood of a White House takeover of the Fed, and understanding what its impact on prices will be in the future. We simply do not know…

~~~

For those of you who do want to explore the Fed independence issue, I direct your attention to Jon Hilsenrath’s August 8th commentary, “The Fourth Seat.” Jon spent 25 years at the WSJ as a reporter and editor, and for a long while, was the Journal’s primary Fed Whisperer.

He was early in explaining the mechanics of any White House power grab of the Fed:

“The President is presently lined up to have three sympathetic voices on the Fed’s seven-member board next year: Governors Chris Waller and Michelle Bowman, whom he appointed during his first term, and a third seat he’s now filling with Miran and later potentially by the new chairman.

It is a seven-member board. If Powell vacates his seat as a governor when his chairmanship ends next year, he is potentially handing Trump a decisive, highly disruptive vote on the Fed board.

With four votes, the Washington-based board has the authority to fire Fed regional bank presidents and reconstitute their boards of directors. Discord at the Fed is coming for the regional banks and this might be the mechanism.”

That is as good an explanation of the present circumstances as any you might read.

In the meantime, I am watching as Mr. Market tries to suss out the various possible and probable outcomes…

See also:

Why Aren’t Markets Freaking Out? (Paul Krugman, Aug 28, 2025)

Previously:

Might Tariffs Get “Overturned”? (July 31, 2025)

Embrace Your Inner Statistician! (March 18, 2011)

The kinda-eventually-sorta-mostly-almost Efficient Market Theory (November 20, 2004)

Nobody Knows Anything (full archive)

__________

1. My full annotation:

“In the short run, the market is a probability machine, but in the long run, it is a data multiplied by psychology machine.”