The transcript from this week’s, MiB: Kate Moore, Citi Wealth CIO, is below.

You can stream and download our full conversation, including any podcast extras, on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, and Bloomberg. All of our earlier podcasts on your favorite pod hosts can be found here.

~~~

Barry Ritholtz: This week on the podcast, yet another extra special guest. Wow. What a fascinating career. Kate Moore is having. Her background is everything from Morgan Stanley to more capital to Bank America, Merrill Lynch to JP Morgan to BlackRock. She’s now Chief Investment officer of Citibank’s Citi Wealth, which runs, you know, something like a trillion dollars. The breadth and depth of her experience makes her uniquely situated to be a chief investment officer. She’s had, you know, just about every job on the buy side and sell side, including portfolio manager, consultant to LBOs and m and as she’s just done so much stuff, it’s so interesting that she really brings just this unique set of experiences to Citi. I thought this conversation was really interesting and I think you will also, with no further ado, my conversation with Kate Moore.

Kate Moore: Thanks so much, Barry. I’m psyched to be having this conversation today

Barry Ritholtz: Long overdue. Yeah, we’ve, we’ve been like ships in the night. I, I’m so glad I finally got, got you here. Let’s start a little bit with your academic background. Yeah. Which is kind of surprised me. Bachelor’s in political and social thought from the University of Virginia, a Master’s in Political Economy from University of Chicago. What was the original career plan?

Kate Moore: I mean, I think Barry underlying your question was like, Kate, you sound kind of nerdy but not as nerdy as some of the folks who have like triple degrees in statistics. But so where did this political and social thought and political economy stuff come from? So at University of Virginia, this PST program is interdisciplinary and that was really attractive. You also apply during your second year so you have a chance to like send it, cut a sample, some different disciplines before you do it. And it’s an incredible seminar program. So you’re working with some really amazing professors throughout the way. I loved being able to take classes in economics, in politics, in theory, in philosophy. I also took a lot of studio art classes and stuff as an undergrad, but I was able to combine all of this stuff together. So I loved that. And then I worked for a couple years and I decided, you know, hey, what I really am good at and what I love is academics and I wanna be a professor.

This was my, my idea. I’m gonna go back to school and get my PhD and be a professor. I had this whole vision for myself that involved like, you know, writing books in the summer I would be doing cool research. I have a pack of golden retrievers and you know, I’d like rock climb on the side. This is whole vision of my academic life. So I applied to PhD programs and I went to University of Chicago for political economy. So this intersection of policy and politics, you know, international theory and you know, economics. And I found once I was there, honestly, that many people in my program are taking eight to 10 years to get through their PhD and becoming so specialized in very arcane topics. And it was like not appealing to me since I had already worked and everything. So I left after my master’s, but I did my work on, you know, this intersection of economics and policy with a focus on emerging markets and China. So I was ahead of my time.

Barry Ritholtz: It’s so interesting that you talk about how specialized some people become. It’s pretty clear, at least historically, many of the greatest investors in history had a very broad set of interest and a broad set of skills. Few of them were an inch wide and a mile deep. They weren’t a mile wide and an inch deep, but they were broad enough that they were able to pull in things from other fields that applied to investing. Did you find something similar when you’re studying political science and economics to, how did that shape your investing philosophy?

Kate Moore: Absolutely. I think, you know, the best macro investors or able to pull in, you know, different inputs from policy and politics, it’s also really helpful I think to understand human behavior. So if you’re taking an interdisciplinary approach to your academics and your investing life, I think you’re well set up. So in this, I mean I took a bunch of courses on game theory and stuff as a, in my graduate work and understanding payoffs and incentives, doing some work on behavioral economics, all of that combines really well. And my experience too was that the best investors that I worked for over the course of my career also took in all of these different inputs and we’re constantly trying to solve a puzzle, right? It wasn’t just, you know, a two variable puzzle. It was a multi-variable puzzle understanding that every day you wake up and you have to do it anew.

Barry Ritholtz: Yeah, no, no doubt about it. It’s so funny you mention incentives. Whenever I see a situation that I find completely perplexing and can’t figure it out, what usually leads to the answer is what, what are the incentives that led to this situation? I want you to work backwards from that. So let’s talk a little bit about the strategy and consulting side. You begin your career, Mitchell, Madison and Silver Oak Partners, is that right? Yes. Those two shops. Tell us a little bit about what you did for them and the sort of work and problem solving you did for those firms. Okay,

00:05:34 [Speaker Changed] So both Mitchell Madison, silver Oak no longer exist, right? For the record, Mitchell Madison was formed out of a spinoff of a bunch of McKinsey partners and it was taking kind of a new way, a new approach frankly, to some of the similar types of clients as McKinsey had. And, but it had this very entrepreneurial kind of environment because it was a break off, but it was still really large and global. I did a bunch of like strategy consulting projects, things you would expect, including some cool stuff in the media space just at the time where the internet was becoming popular. And some of these websites like Amazon that we take for granted were getting launched. So I learned a lot about media and e-commerce in those early stages at Mitchell Madison, but Mitchell Madison, for those of you who may recognize it, went through a merger with us Web CKS, which was a technology consulting firm.

00:06:33 All the combined entity got rebranded as March 1st, which was the date that the deal was inked. Kind of a weird marketing decision on that part, but you know, the, the, the business started to change and a number of the partners like broke off and started Silver Oak, which focused on leverage buyout firms. Now here is what was really cool. I wasn’t doing work for let’s say the LBO in master form, but rather like a collection of the companies in the portfolio at the same time trying to find synergies. There were things that are traditional around sourcing, but things that were maybe less traditional around finding strategic combinations. And I had a great opportunity to get exposed to a lot of different industries, you know, from traditional manufacturers to telecom companies, financial services and everything in between. And I have to say, Barry, that experience, you know, working for these kind of small and mid-sized LBO owned companies really set me up well for understanding and investing in a broad array of equities.

Barry Ritholtz: So let’s talk about the investing side. Your next stop is Morgan Stanley, obviously a legendary and giant sell side firm. Tell us your, about your experiences at Morgan Stanley. Yeah,

Kate Moore: So how I got to Morgan Stanley investment management is perhaps kind of interesting. So we were just talking about my academic background and I was doing this, you know, political economy degree at University of Chicago and I had had this sort of moment where I realized I wasn’t gonna pursue the PhD. So I, you know, made an appointment with my advisor and I said, you know, professor Harold, I’m not sure I wanna do the PhD. And he starts laughing and we’re sitting in his office, he said, Kate, I’ve been waiting for this conversation for six months. Oh completely. Wow. I said, oh my gosh. Like do you know, do you think I’m screwing up here? He said, no, you’re top of the class. What I do recognize though is because you’ve worked before for a number of years before coming into a PhD program, you have a different skillset and you’re approaching this differently. He’s like, I think you can finish your PhD later. You know, do the master’s and whatever. So I had this in my mind and I, so I started to put out a couple feelers, but I wasn’t really committed to what I would do post, you know, getting my master’s degree.

Barry Ritholtz:And this is out of Chicago, rght?

00:08:43 [Speaker Changed] It’s in Chicago. And then a strange thing happened, I was back on the east coast visiting my parents and I got a call from the career services people at University of Chicago. I was still, you know, enrolled in school there just getting my thesis graded. And they said, Hey, we got an incoming call from the Chief Investment officer of Morgan Stanley Investment Management. This guy’s name is Joe McLinden. Joe is looking to add to his macro investing team on the buy side and specifically is looking for candidates that are not MBAs. He wanted people who had this understanding of politics and economics and everything in between. And I said, Hey guys, I’m not interested in going back into that form of finance. I’m gonna do something different. They said, do us this favor and go on the interview.

Barry Ritholtz: Just like, just just meet with them. Yeah.

00:09:35 [Speaker Changed] Like let’s put up a good candidate. You kind of meet the criteria. If it’s not your bag, it’s not your bag. And I went and met this team at Morgan Stanley investment management and people who had economics and history and philosophy degrees, but were macro investors. And I was like, okay, A, these people are cool and b, I love how they’re solving the problems. Two weeks later I accepted an offer. I fell into investing Barry.

Barry Ritholtz: Wow, that’s that’s really fascinating. And, and you’ve had a breadth of experiences beyond Morgan Stanley. You were at more Capital well regarded hedge funds, bank of America, Merrill Lynch, JP Morgan, you spent a lot of time at BlackRock. Tell us what was fun, what did you learn at these other shops?

Kate Moore: So I’ve had a really cool career in the sense that I’ve done, you know, a variety of different buy-side, more traditional mutual funds. But even when I was at s Im, we launched the first internal hedge fund. This is before Morgan Stanley bought Front Point and I worked at a big macro hedge fund through the financial crisis, as you mentioned, at more capital that was an adventure. I did a few years on the sell side at B of a Merrill as global equity and emerging market strategist. And then I went to JP Morgan, managed the discretionary multi-asset portfolios for the private bank. Then I spent a, a long time at BlackRock, most of it as a portfolio manager for global allocation, kind of the flagship multi-asset fund. I have to say I love the fact that I have experienced all sides of the investing business and it makes me understand what makes investors tick a lot more than people who just stayed in their lane. Like I get the retail side, the institutional side, what fast money does, what traders do, what fundamental investors do. And I interpret all this sort of sentiment and flow data as part of my process as a result of having this exposure to different parts of the investment management business.

Barry Ritholtz: Sounds really, really interesting. So from all of these different backgrounds, what finally brought you to Citi?

Kate Moore: Yeah, so I, I was at a bit of an interesting inflection point I would say in my career here I am. I’ve loved being at BlackRock, I really enjoyed the work, but I also recognized I was kind of ready to take the next big step and I could continue to be a portfolio manager at BlackRock and it’s an amazing firm, but I was kind of wondering what it would sort of, what what I should do to take this next step. And I looked around and said where are the areas of growth in the business? And traditional mutual funds we know are not a huge growth area for the business. Even if your performance is exceptional, you know, keeping your assets can be a challenge. And I saw wealth as an area of consistent growth. I think most people would agree on that front for sure.

00:12:22 And, and you know, there’s some growth in alternatives, but it felt like just a different flavor of the stuff I was doing. So I was sort of intrigued by this idea of, of working in wealth, especially because I’ve done a lot of asset allocation and the multi-asset discipline I come from and I love the challenge of helping people grow their money over time. But I hadn’t, I didn’t have like a great idea in my head of what I was gonna do. This was just sort of something that was a seed that was planted and not yet out of the soil if it were. Hmm. And in August of 2024, Andy Seig, who I’d known in the business for like 15 years or so, never worked together directly. But you know, we’d met a number of times, been on panels together, had good cordial relationship. He called me and said, Kate, I have an idea for you.

And he had been at Citi for a year then as you know, CEO of wealth. And I thought, okay, this is interesting, but I need to turn it over in my head a little bit. Is this gonna be the right pivot? And ultimately I got so excited Barry because Citi was already in this massive transformation. Andy is a really inspirational leader. I’m not just saying that ’cause he’s my boss, but I think most people on the street will agree. He has a vision he executes and this was a new challenge for me. I’d be flexing different muscles and I thought to myself, for this next big push in my career, I wanna be someplace where I can be entrepreneurial, where I’m gonna be supported by the overall platform where, you know, I can continue to grow out my experience as an investor. And so ultimately I made the tough decision to leave a firm that I loved for a new and exciting challenge.

Barry Ritholtz: Safe to say that this shift in career was the biggest inflection point.

Kate Moore: It feels like it’s the biggest inflection point in my career, but it also feels cumulative. I don’t know if that makes sense, but perfect sense

Barry Ritholtz: I understand exactly what you’re saying. All all of these different elements come together almost like a perfect storm. Yeah. And suddenly now we’re off to the, to the whole nother level.

Kate Moore: Yeah. I’ve been building up these experiences over the course of my career and kind of setting me up to take on this new challenge. It does feel the largest in part because I’ve been so concentrated on being an investor over the course of my career. And this is a combination of strategy and, and business leadership and investing. And so as I said, I’m flexing, flexing a bunch of different muscles.

Barry Ritholtz: So let’s put some numbers, some flesh on the bone. So the groups you lead the wealth group at at Citi, what’s the assets they’re investing and typically who are the clients? Are they mom and pop investors? Are they institutional? A little of both.

Kate Moore: Yeah. So I’ll give you some numbers as of end of 2024 because everything else, of course is in flux in the first part.

Barry Ritholtz: We know how that works.

Kate Moore: Yeah. I’m in, in the middle of studying for series 65, what will be like my 39th millionth of

Barry Ritholtz: But that one you could do in your sleep. It’s not like the seven, which is or the options. Yeah. I forgot which one was the options. That was a giant like wait, I need to learn about gamma, why not?

Kate Moore: Totally. I’ve taken the options one too. What I will tell you is the one thing that’s a little bit annoying on the economic section of the series 65 is that, you know, I don’t always agree.

Barry Ritholtz: Was gonna say the answers are wrong answer. Once you get past that, the test is really easy.

Kate Moore: For Example, it was like, you know, our payrolls a leading lagging or coincident indicator. Very, of course

Barry Ritholtz: It’s lagging! Of course or anything but lagging because it’s two months old.

Kate Moore: Totally. And like plus or minus 100

Barry Ritholtz: They, they said coincidental, right? Totally. Yeah. It’s just there. I, I remember having an, this is by the way, 30 something years ago, 20 something years ago. I remember calling up and yelling at somebody like, just so you know, I didn’t get any of these answers wrong. And the three you marked wrong, you are wrong. And let me explain why totally. How, how can payrolls, which are a model that uses 1, 2, 3 month old data be anything other than a

Kate Moore: Lagging and that get totally restated every two years. Right. And the, the error bands, but the subsequent monthly revisions, I mean by the time you get to the actual number, it’s like half a decade old. It’s nonsense

Barry Ritholtz: a hundred percent.

Kate Moore: We have to pretend.And yet of course the market moves a lot on payrolls stay and we have to pretend that matters in the moment. Yeah, we have to pretend. Okay, where were we going before?

Barry Ritholtz: I have no idea. But I just love the fact that you’re studying for the 65. I know studying in air quotes,

Kate Moore: I get to whiz through the equity and hedge fund and everything sort of sections of it. But I have to memorize their answers for economics.

Barry Ritholtz: If it, if it wasn’t embarrassing to fail, yeah. I would say you can wing it and you’ll do just fine. I think 70 is a passing, you’ll get like 80 just off the top of your head. But no one wants to go in and fail ’cause it’s embarrassing

Kate Moore: No, I’m very like, I, I’ve made my career off of being a perfectionist, you know, in my analysis. That’s so funny. And you know, I do not accept a barely passing grade. I do not expect, I, I accept, you know, index like performance. I’m always seeking alpha and I’m doing my best to do that in the most risk adjusted way, even

Barry Ritholtz:In an examination that’s pass fail. Yeah. And we know objectively, logically anything over a 71 is wasted effort. But yeah. But I know where exactly where you coming

Kate Moore: From. I can’t sleep at night. I can’t sleep at night if it’s just good enough. And that’s also how I wanna approach things for my clients. Okay, we’re talking about Citi here. And so Citi has about a trillion do, Citi Wealth has a trillion dollars in assets close to like 600, you know, billion of that is in investments and there’s other parts in deposits and loans and things like that. And there are three main segments, right? There’s a traditional kind of private bank, ultra high net worth service, right? There’s Citi Gold, which is mass affluent, and then there is a wealth at work which targets like very specific segments like the law firm population, et cetera.

Barry Ritholtz: Makes a lot, makes a ton of sense.

Kate Moore: What I will say is Citi as a bank has so many global customers and clients and people with longstanding relationships that haven’t been tapped. You know, there’s, there is an enormous amount of potential to grow the wealth business just from existing Citi customers. And I think as you probably know, half of our business is outside of the US and it is a, it is a,

Barry Ritholtz:Is it 50%? It’s fully half, yeah. Wow. That’s amazing. Yeah.

Kate Moore: And the Asia business for us and particularly our legacy in China and surrounding areas is incredibly strong. And that was something that was also very attractive to me, to be honest with you. As someone who has been an, an emerging markets investor at times and a student of China, you know, the ability to get really deep into the opportunity to grow wealth in multiple different areas was exciting.

00:19:15 [Speaker Changed] Huh. Really, really fascinating. So before we talk about Citi, let’s start a little bit with your time at BlackRock. You joined them almost a decade ago in 2016 you were chief equity strategist. Tell us a little bit about your initial role and how that played off of what you had been doing previously.

00:19:35 [Speaker Changed] Yeah, so I joined BlackRock to be part of the BlackRock Investment Institute, which is kind of the internal macro think tank. And the institute has a couple of different functions. There is a segment that is client facing, but there’s also a big function around bringing together the investors across all the platforms in BlackRock and convening for, you know, forums and symposiums around specific topics. And although I was called Chief equity strategist, I actually sat on the equity platform with all the equity PMs and my job was to be basically embedded in all of the equity portfolios as the macro. My team was the macro resource for them and it was great. And you know, I always knew that I would do that for a little while. They basically said, can you do this and help to sort of change some of the equity culture and to have some macro inputs and then you can kind of figure out where you wanna sit. And ultimately, you know, moving back to a multi-asset fund made the most sense for me because here’s my joke, Barry, like I think of myself as being a macro equity investor, you know, combining macro stuff into equities, but the macro people will say, I’m equity and the equity people will say I’m macro. Yeah, that makes sense. So a multi-asset fund is a, is a good home for me. Huh?

00:20:50 [Speaker Changed] So 2019 you start working with the thematic strategy and portfolio manager group. Yeah. Tell us a little bit about thematics that’s become sort of an alternative to beta in a lot of shops. BlackRock especially.

00:21:06 [Speaker Changed] Yeah. Well let me say this, I actually started my career, you know, at Morgan Stanley investment management and the hedge fund that my team launched at MIM was a global thematic hedge fund. This is way back like over 23 years ago at this point. So we were ahead of our times, right? So I’ve actually had this thematic approach, frankly in my investment approach throughout my entire career. And it’s just now becoming really popular to call everything a thematic. So lemme say this, I think there are three ways at this time to approach thematics, three different flavors if you will. The first is this kind of like long duration slow bleed thematic. Like eventually we are going to have reduce the amount of plastics in all of our goods. And so we wanna lean into companies that are investing in that transition. You

00:22:01 [Speaker Changed] Don’t think microplastics accumulating in your lungs and bloodstream is a bad thing.

00:22:06 [Speaker Changed] It is definitely a bad thing. I wonder if I’m a little bit cooked when it comes to that already. But this is kind of a set it and forget it strategy, right? Where you identify companies that are making these changes or facilitating the changes and you buy a basket of them and you or an ETF that invests ’em and then you just set it. The second type of thematics is what I would call like discontinuous change, catalyst driven thematics. And these are more tactical, like, you know, it could be a couple quarters, it could be up to a year or two or even longer. But this is kind of a more actively managed way to approach thematics, right? Where, so you identify the idea, you identify the catalysts, you identify the players, and actually there’s more of a rotation in the names and the sizing of that expression in the thematic. That’s really exciting. It’s also hard because sometimes you look around and say, I don’t see a ton of catalysts here. There’s nothing really jumping out. You

00:23:02 [Speaker Changed] Gotta get the theme, right? The asset class, right? And the timing right

00:23:05 [Speaker Changed] And the sizing, you know, within that, right? And so that’s not like by 40 companies that are thinking about microplastics. It is like four to eight names, a more concentrated expression around a theme. You’re taking some idiosyncratic risk and you are continuing to to invest around that. And then the third type of thematic investing, I would say is really business cycle thematic. And a lot of people talk about this, you know, today there’s a, you know, where are we in the cycle? What are the companies sectors or qualities that perform well in that part of the cycle? I’m thematically investing in inflation beneficiaries, et cetera. And I’ve always liked to do those two, kind of number two and number three together, which is the catalyst driven and the business cycle. And I think that together makes a nice portfolio.

00:23:54 [Speaker Changed] You know, I recall back in the day when we were talking about sort of thematic cycle investing, business cycle investing, it was used to go by the name sector rotation. Yeah. I don’t know if anybody still does that sort of stuff anymore, it

00:24:09 [Speaker Changed] Seems like, or the investment clock. Do you remember the

investment clock? Sure, sure. Absolutely. Everyone had an investment clock, which

was like this two dimensional representation of which sectors or which maybe style

factors. Once that became part of our lexicon performed well in different macro environments,

00:24:26 [Speaker Changed] It was always sort of a sine wave. And here’s where we are in this sector here in the sector there. Yeah. If it only were, were that easy.

00:24:34 [Speaker Changed] Yeah. You know, I, I won’t call out names, but I know some folks that like to chart where we are, which quadrant we’re in, right. You know, on a regular basis. And instead of this nice round circle or an oval, you know, it’s very sort of spastic point to point, to point to point because the macro data is moving so quickly and the positioning data, which also indicates, you know, investor risk, appetite changes so rapidly that we jump from one quadrant to the other sometimes month to month.

00:25:05 [Speaker Changed] So, so you mentioned removing plastic from the food supply or wherever. Yeah. What other trends have you looked at? Deglobalization, decarbonization ai. What gets you excited these days?

00:25:18 [Speaker Changed] Oh wait, you just said a hot button word for me, which is deglobalization. And let me just say I don’t believe in deglobalization.

00:25:24 [Speaker Changed] I’m with you, but I want to hear your reasons why.

00:25:26 [Speaker Changed] Yeah, I don’t believe in deglobalization because even if, let’s say hypothetically the US and China continue to separate and by hypothetical I was making a joke for all the listeners, of course the US and China are gonna continue to separate. That doesn’t mean the relationships between each of these countries and other trading partners or allies is not gonna deepen, right? Maybe we call it re globalization instead of de-globalization, but a, a shifting of some other relationships. But I have spent a lot of my time, like a lot of folks frankly, looking at themes in and around technology. I mentioned the microplastics. It’s actually not a theme I’ve invested in. The only couple companies I’ve really seen who are geared towards that are private. And so it’s harder to access. But around technology, you know, a few areas I’ve been pretty excited about for a good considerable amount of time has been, you know, have been in, in software.

00:26:20 And one of those areas is cybersecurity. This was a major theme for me in the portfolio at Global allocation at BlackRock. And basically every time I was thinking that I’d want to either shift out of the theme or reduce it, there was another event on the horizon or something happening that led to increased spend in this space. I’ve now come to believe that investment in, in security software is existential for companies, right? And while there’s room to rotate, you know, names based on capabilities, et cetera, I believe it’s a, it’s a core part of a portfolio

00:26:54 [Speaker Changed] Longstanding secular trend that’s gonna be ongoing.

00:26:57 [Speaker Changed] Absolutely. But I first put on this investment in January of 2020 Okay. When I was at BlackRock and that was before the pandemic and it was basically based on geopolitical risk and of course the pandemic that increased the risk from all this data for many different companies. So we saw big up uptick in spends. As I said, it was a, it’s been a rolling series of catalysts over the last five and a half years and makes it more of a secular theme than a, a shorter term catalyst driven theme. So.

00:27:25 [Speaker Changed] So let’s drill down a little bit to your core investment philosophy. You’ve mentioned thematics, you’ve mentioned pursuing Alpha. Tell us what is Kate Moore’s investment philosophy?

00:27:37 [Speaker Changed] Yeah, I think it’s really important to have three pillars to your decision making and one pillar that’s off to the side that’s controversial. So I think you have to start with a macro view. I think you need to understand politics policy, the major economic data you need to understand government behaviors. ’cause so much of that dictates the environment for different industries. And some people just sort of brush it off. By the way, I love my equity colleagues and friends, but nothing makes the hair on the back of my neck go up more and kind of me bristle than to hear. I don’t pay attention to macro because I just pick good companies. Well good, you’ll be out of business. You don’t have a choice in this environment. You can’t set it and forget it for the next three years and not focus on what’s happening in the business cycle and policy and how that may impact the interest and desire to own your asset class.

00:28:29 So I think macro is critical and a good starting point. I also like to get into the fundamentals of things, right? Like where are the fundamental thematically, like who’s growing, what technology has come out, where do we think about, you know, changes in consumer behavior, changes in supply chains, and where are the real kind of fundamental opportunities? What are the companies doing? Well I think that’s not controversial either, but with the third stage, and it’s really important to me, I mean it’s grown in importance over the course of my career is the positioning, sentiment and technicals. And this has become really, really, really important for your, for defining your entry and exit points, even if you are a long-term investor because the markets move really quickly and you need to be really thoughtful about how you enter and exit. So I pay attention to flows, hedge fund, mutual fund positioning, introduction of new instruments, you know, a million things we kind of look at at our dashboard. And then this is the one I was saying the pillar off to the side valuation is a nice to know, but it is not a driving force of my investment process. And people might kind of cringe when I say that, you

00:29:40 [Speaker Changed] Know, know what, let me jump in here and, and I won’t explore that ’cause I don’t disagree with any of that. People kind of forget that bull markets that run 10, 20 years, valuations tend to start on the lower end and they tend to end on the higher end. But if you decide, oh, we’re above the average valuation of the past cycle, you’re missing a lot of upside, aren’t you?

00:30:06 [Speaker Changed] Ton of upside. Well there’s also this assumption that that underpins this view on valuations. That there is some sort of mean reversion, right?

00:30:13 [Speaker Changed] Tomorrow we’re gonna snap at, look at the cape is my favorite example of that. Yeah, the Schiller cyclically adjusted PE ratio. You would’ve been out like 90% since 1990. A hundred. Yeah. If you followed that, it’s, it’s kind of wild.

00:30:26 [Speaker Changed] Yeah, for sure. You would absolutely have not taken advantage of an incredible run in equities. Like, just to make this point and underscore it, I say evaluation is a starting point for your investment decision, what you’re screening for and entry and exit points. You would never own US tech and you would be long Russia, you know, and anyone who wants to take that trade, God bless, but you’ll be out of business, right?

00:30:50 [Speaker Changed] Russia’s been cheap, but some stocks are cheap for a reason.

00:30:54 [Speaker Changed] They are European banks cheap for reason. And we know that kind of over the medium term, this I’ll define as kind of three years, you know, stocks can stay quote unquote expensive or the way I like to say it be valued at a higher end of the market range because they are superior businesses and they can stay at those levels for multiple years, sometimes much longer and continue to rerate and stuff can look like it’s a discount to the rest of the market, but be structurally impaired and therefore deserve the discount. The other problem I have when people do these kind of like mean reversion, you know, valuation trades as they say like, oh we need to go back to some historical period where s and p was at 14 times, right? Why? I mean the market composition from a sector perspective completely different. The balance sheets of these companies completely different. The cash profiles and free cash generation of these companies completely different. The regulatory environment, the politics, the behavior, the market technicals, I can go on and on and on. It is literally the laziest piece of analysis I have ever seen.

00:32:04 [Speaker Changed] When when you look at last century companies like US Steel or even General Motors, you know, the expression was men in material, they need tons of capital giant factories today, two people with a laptop and Amazon web servers. You could, you could do as much business as any startup from any decade previously.

00:32:27 [Speaker Changed] Totally. I mean another example I like to use, like near and dear to our hearts in terms of the investment landscape is, you know, how many analysts do I really need to cover all different sorts of sectors? You know? And it, there was a time where I needed everyone to be an expert in a different industry or a different sector and to be very siloed and and deeply specialized. But right now I can be in a meeting sitting across the table from A CEO or CFO and they may be talking about a business that I only know 50% about, right? And I, in real time, I can use my AI tools, I can pull up what their competitors have said in recent earnings calls or you know, in the social media, I can look up terminology, I can pull up data. I am a hundred times more informed. I don’t need to be briefed for three hours from an analyst before I walk into that meeting. You know, just by understanding the types of questions to ask and having this data at my fingertips, I’m a faster and better investor.

00:33:25 [Speaker Changed] So here’s the challenge, and we could talk about AI as a theme in a little bit, but the challenge is you’ve gone through that whole process over the past 10, 20 years where you’ve, you know, done the reps put in the heavy lifting. Yeah. How is the next generation going to become the Kate Moore in 25 years if they don’t get to go through that process? And AI seems to, the phrase I heard recently was removing the bottom rung on the career ladder. Is this, is this a genuine concern?

00:33:59 [Speaker Changed] It is somewhat of a concern and I think it’s more of a concern for, for kids who are going through school and are incredibly specialized about what they’re studying. And this is kind of a flag frankly, I would say to people, you don’t wanna just take courses in one discipline. Your job as an undergrad. And I would also argue even in grad school, even in MBA program, is to learn how to think and learn how to ask questions to get exposed to as many different disciplines as possible. So I tell like young folks, like you gotta study philosophy, you should also study things like art history because there’s context behind it. You should study things like you know, hard sciences because you know, it gives you a discipline in terms of the way that you’re thinking you should take a music theory class. I mean do all of this. You want your brain to be flexible and compliant. You want to be able to approach the problem by using these tools in unique ways. And people who are only point and shoot, only have one specific way of approaching an investment problem are often wrong.

00:35:04 [Speaker Changed] Huh. Really, really, really interesting. So you were brought to Citi specifically to focus on the wealth business there. What’s your strategy for breathing life into that space?

00:35:18 [Speaker Changed] So I think there are a couple things. We have a lot of amazing raw material at at Citi in terms of human capital and of course our clients. But thinking about how to invest in a different way than perhaps my other wealth competitors invest is, is one of the greatest challenges and opportunities. And here’s what I will say, you know, I want to examine the way that we’re approaching discretionary multi-asset class asset allocation products, right? Just to sort of set it and forget it. Here’s your stock bonds cash, I’m not sure is gonna be the right path moving forward. I mean, we want to think about what is the right combination of both asset class and factor exposures for, for clients in different risk profiles and how do we implement in, in an interesting way in that space. So it’s not just like, hey we have a, you know, large cap stock fund or, and we have a, you know, mid, mid duration bond fund and this is what we’re kind kind of combining together. This is really about, you know, what are the best expressions of each of those things? How much of it should be beta? How much of it should be alpha seeking? Whether it’s you know, sector specific or thematic. What is the best implementation in alternatives? And particularly as we get more liquid alternatives available, you know, that sort of diversification in a portfolio is going to be kind of democratized and we’re gonna see more and more of our clients across risk spectrum be able to access that. So,

00:36:51 [Speaker Changed] So let’s talk about the opportunities in the wealth business. What’s driving the growth here? Is it just the amount of capital that’s sloshing around? How big are demographics, the move towards alternatives? There’s so many different cross currents going on that make that space so attractive. What do you see as the key drivers?

00:37:12 [Speaker Changed] Yeah, there’s a bunch of different drivers, Barry. I’d say, you know, first of all there’s been an enormous amount of wealth created. We know over the last, you know, 10 years, it’s longer than that. But let’s just say in the last 10 years

00:37:23 [Speaker Changed] Post-financial crisis.

00:37:24 [Speaker Changed] Post-financial crisis, great 15

00:37:25 [Speaker Changed] Year run.

00:37:26 [Speaker Changed] Absolutely. And big concentrations of wealth and frankly a lot of very wealthy families have held a lot of these, this wealth in cash, you know, or in cash equivalents or have reinvested in their business. I think there’s now an understanding that they wanna diversify. So the investment opportunity set for all this wealth creation is huge. I’d say there’s another trend, and I’m sure people have talked about this before with you, which is like the transfer of wealth that’s gonna happen from the b the boomer generation to my generation, and then ultimately to our, you know, younger generation. And the values and the interests on the investing side change from generation to generation. You know, the types of risk clients wanna take, the types of like bespoke opportunities and private stuff that they wanna do. Maybe it’s around, you know, environmental social governance stuff. Maybe it’s around specific geographies, mission aligned. I mean I think that the flavor of investing is changing, which also makes us super exciting. And then finally I would say can, you know, the, the breadth of investment instruments that are available to individual investors and into wealthy families is actually really exciting because you can do cooler things than just a 60 40 portfolio, which was kind of the way wealth businesses ran in the past.

00:38:46 [Speaker Changed] Hmm. So you had mentioned the role of behavioral finance in some of your education and background. You were at University of Chicago, which has become a hotbed of behavioral finance. Dick Thaler. Yeah. He’s recipient of the Nobel. Tell us how you think about behavioral economics in your day job. How do you help clients steer through some of this year as a perfect example, a lot of volatility, a lot of sterman, drang, and here we are above where we were before liberation day. How do you guide people through that?

00:39:21 [Speaker Changed] Yeah, this is such a tough one, Barry, because you know, this is where understanding kind of the positioning, the technicals and the biases really differentiate a good investor from maybe a less good investor. One of the things I try and pay close attention to are all of these sentiment indicators and like, you know, the dashboard for sentiment indicators continues to change, right? Sometimes we look at, you know, historic filings, but we know that mutual funds and hedge funds change their positions really quickly. Sometimes we look at the volume and the flow. I like to pay attention to more kind of third party and, you know, coincident things like what, what’s being discussed in different social media or on different message boards or whatever. And to just try and understand what’s capturing the attention and energy from different client segments. But I also pay really close attention to frankly, how the market responds to different types of news. And that gives you a good sense. You gotta have your finger on that pulse. You know, I, I learned this from someone named Ben Hunt, who you may be familiar with. Of course,

00:40:32 [Speaker Changed] You’re right. Epsilon theory.

00:40:33 [Speaker Changed] Epsilon theory. So I learned this from Ben years ago, but he said, you know, number one, the first order to getting things right is like having a good forecast, right? Let’s just say you have a forecast for stock earnings. The second order is to understand what consensus thinks, right? And comparing your number against that, right? But to get it really right in the market, you need to understand what consensus thinks. Consensus thinks

00:40:59 [Speaker Changed] It’s a Kane’s beauty contest.

00:41:02 [Speaker Changed] Absolutely. And, but, but kind of instilling that in my team is really important because it’s like, great, I’m so glad you think we’re gonna have $263 of s and p earnings this year. If consensus actually thinks it’s 2 67, we should know that too. But if the printed number is 2 67 but everyone’s just dragging their feet on cutting the numbers and they’re actually at 2 55, that makes a difference in terms of how people take risk and respond to different news. And so, you know, kind of, of putting all these pieces together, doing the work, understanding what like written or published consensus is and then getting all these kind of sentiment inputs to really evaluate what is the whisper real number versus what’s published.

00:41:46 [Speaker Changed] So let me push back slightly on sentiment ’cause I want to get your take on this. So my experience generally has been most day-to-day sentiment is kind of noisy and it really matters when it hits an extreme. At least that’s a trader’s perspective. But the thing I really wanna push back on has been the University of Michigan. Yeah. Consumer sentiment data, which over the past couple of years it’s been worse than the financial crisis, worse than the beginning of the pandemic, worse than the the 2001 September 11th attacks or the.com implosion worse than the 87 crash. How do we figure out what’s going on in sentiment where it seems to have just detached from consumer behavior, Hey, everything is terrible, but we’re going out and spending totally,

00:42:38 [Speaker Changed] We’re still going out to restaurants even though we think the world is ending, right? Yeah, no, you’re absolutely right. So any single sentiment indicator or survey needs to be discounted, right? We need to come combine all these things and look at it kind of on a moving average of a number of prints. Another one that kind of flagged for me was the conference board confidence, which hit the lowest levels from like September of 2011, you know, last month. And that was a crazy number, right? Because it, September of 2011, we had just gone through this debt fiasco. We were going to Operation Twist, you know, there was like

00:43:11 [Speaker Changed] Post flash crash, it had gotten even crazy.

00:43:14 [Speaker Changed] Absolutely. So, you know, that, that seemed really disconnected from reality. So sometimes you have to discount all of these things, but your point is well taken. There has been a generalized sentiment deterioration. Another one I look at is the, what is now the Richmond Fed, but historically had been the Duke Fuqua CFO survey. And you’ve seen over the past couple years this massive decoupling between expectations for own company over the next six months where the CFOs are going, like things are pretty good actually. And expectations for the economy where they’re like, the economy’s in trouble.

00:43:46 [Speaker Changed] It’s so funny you bring that up ’cause well first I had Tom barking and not too long ago, but second, we see that everywhere my congressman’s okay, but the rest of Congress thinks totally my financial circumstances seem to be pretty good, but we think the economy is going lower. Like that exact sort of sentiment split. What do you imagine is driving people to think, Hey, things aren’t that bad for me, but everywhere else it stinks.

00:44:14 [Speaker Changed] Yeah, I, hmm, this is tough one, but I, I honestly think the news flow, how media portrays recent events, the echo chamber on social media, the fact that people are not getting a broad based view. Do you see all these, you know, traditional news programs now that are trying to dedicate one night a week or whatever the heck it is to the good news, right? They’re

00:44:36 [Speaker Changed] Is that true? That’s,

00:44:37 [Speaker Changed] Yeah. It’s like, that’s funny. There’s a, there’s a, a local channel I’ve watched that it will do one good story after they’ve just reported a bunch of like murders and you know, everything for the previous 25 minutes. The last story is like, they’re trying to leave you on a positive note, huh? I’m mean like, okay, but the skew is definitely really negative.

00:44:55 [Speaker Changed] If it, if it bleeds it leads, that’s always been the news thing. Yeah.

00:44:58 [Speaker Changed] Really, really fascinating. But now people are consuming more of that

00:45:01 [Speaker Changed] And so I think, I think you’re definitely onto something. But

00:45:04 [Speaker Changed] So we, yeah, we do maybe need to z score the sentiment right now, let’s just put it that way. We, we have to adjust for this declining overall sentiment. But when I’m talking about sentiment, I also like, I’m trying to infer sentiment from price reactions to different news, right? And that might be a better gauge in some of these surveys where people can say, you know, the sky is falling but then just book a carnival cruise, right? Like, you know the, and you know, if a stock puts up pretty good numbers in terms of earnings but doesn’t beat by huge margin and falls 15%, you can tell that like people are at the edge, right? And so, you know, you have to kind of correct your own equity exposure for that type of behavior, huh. But your point’s well taken on you mish and on, you know, all of these other surveys, there’s been a generalized decline. We have to correct for that.

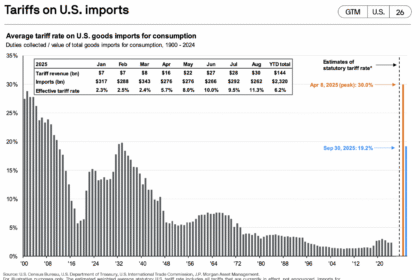

00:45:52 [Speaker Changed] Huh. Really interesting. So let’s talk a little bit about today’s market environment. 2025 has been kind of a volatile wacky year. What, what’s your current macro view on the global economy? What’s going on in markets? The fed yield inflation, tariffs, it all seems to be kind of tumbling together at once.

00:46:15 [Speaker Changed] Yeah, I have to say 2025 has been a tough year for anyone and it’s also been a tough year candidly for me to start a new job. I like to say that every time I start a new job there’s some big volatility event. This one might be the biggest and frankly totally self-induced as opposed to some kind of exogenous or external shock. So it’s been really difficult to navigate through this market and yet, you know, there are some things we can still anchor to paying attention to what companies are saying about their businesses. This kind of sort of sentiment stuff we were talking about a moment ago. Looking at the long-term trends, this all leads us to say like okay, we can still be invested. But I am deeply worried Barry about what’s gonna happen to the economy over the summer and and into the beginning of 2026.

00:47:05 We know that companies have been operating more or less BAU business as usual despite all of the shocks on headlines around tariffs and consumers, you know, may have pulled forward some demand, but they’re also kind of operating BAU for the most part. There’s not been a significant change. And yet we know that the introduction of these tariffs and the risk aversion that’s a result of these tariffs and changes in policy and changes in expectations for global supply chains is going to lead to some weakness and activity. The thing I just wanna point out is like going into the end of 2024, in the beginning of 25, I was also like a little worried frankly that the economy was slowing not catastrophically, not recession style, but there were enough cracks across the consumer and enough indications from companies to basically suggest like this was not gonna be an accelerating year even before these policy shocks.

00:48:01 And now I think despite some adjustments, you know, immediately after the tariff announcements, companies don’t have an incentive to do a bunch of different things. And that is engage in real CapEx, they’ll spend what they need to to stay in business or to maintain or things that are absolutely necessary, but they’re gonna prioritize expansionary CapEx and acquisitions I think are off the table. Number two on the labor market. We’ve heard a lot of people talk about it being frozen. Yes there’s still some hiring, but when you look at kind of the composition of the hiring, it’s not as exciting as it might have otherwise been in a, you know, policy, you risk free economy and I think companies have an incentive to kind of keep their labor force where it is without really expanding. ’cause they don’t know if that’s gonna make sense for margins and stuff going forward.

00:48:51 And then the third thing I would say is, you know, companies need to ask themselves what should my supply chain, what should my corporate relationships look like over the course of, you know, the next couple years? Because the truth of the matter is if they have to realign ’em, it will be a significant cost. It will take a ton of time and take a ton of energy. And yet if there might be a policy shift either at the midterms or under a new administration, the incentive to make these multi-year investments as low. So I get this sort of paralysis that’s playing out in terms of the market in, in terms of corporate behavior. And so I’m a little, I wouldn’t say worried about a recession, but concerned about much slower activity in the second half of the year.

00:49:35 [Speaker Changed] So that raises so many different issues. We keep hearing from CFOs, CEOs about the lack of clarity. If you don’t know what the policy’s gonna be, how do you relocate manufacturing plan a headquarter? How do you plan to do any sort of expansionary hiring? So I’m completely with you that hey, this seems to be this self-inflicted wound that’s preventing the economy from accelerating and yet despite all that the economy seems to be incredibly resilient and not taking too big of a hit from all of these on again off again tariffs. Does that just mean that this administration inherited a really robust economy?

00:50:23 [Speaker Changed] Yes, and I think there’s another element to it. I do think this administration, you know, inherited a resilient economy. One that was perhaps underappreciated over the last couple years because not everyone was feeling that resilience in the same way or wealth creation wasn’t as broad as some would’ve liked. Okay. But I think there’s another element to this too, and this goes a little bit into kind of corporate behavior and how investors react to corporate decisions. Which is, you know, if a company pulls back prematurely, let’s say they shed a bunch of workforce or they cut a lot of CapEx and they really hunker down for a bad economic environment and that doesn’t actually show up for multiple quarters and they la

00:51:08 [Speaker Changed] Kinda like the past few years. Yeah. Everybody forecasting recessions that never came

00:51:12 [Speaker Changed] And they lag their peer group and they look weak relative to the rest of the industry. Wow. That, that makes people lose confidence in that management team. Hmm. So there’s almost an incentive for management teams to maybe have contingency plans to talk about that with their board and the rest of their leadership, but not necessarily communicate that with the investment community and keep operating with only a tiny bit of defensive action because there’s gonna be a penalty on their stock price and frankly in the confidence people have in the management team, if it looks like they’re being too emotional and reactionary.

00:51:48 [Speaker Changed] This sounds like the game theory work you did at UFC Yeah is coming into the

00:51:52 [Speaker Changed] Before a a hundred percent that that it plays a huge part in the way I think about this. So you know, no company has an incentive to talk about how concerned they actually are publicly because the first one that does it will be penalized.

00:52:05 [Speaker Changed] Huh. That’s interesting. And, and since you work at a giant bank, we’ve seen bank earnings that are pretty strong across the board. Yeah. That’s kind of unexpected. Tell us a little bit about what does that mean in light of this environment? Relatively high rates really just more normalized than what we’ve seen in the prior two decades. What’s going on in the banking sector?

00:52:31 [Speaker Changed] Yeah, well I can talk a little bit about Citi because we’ve had some pretty awesome operating performance and there are a couple things really driving that. Of course, you know, there’s been a real focus in terms of cost and expense. This is not just Citi, this is across the board at major financial institutions and frankly investment investors really love this. They want to see that discipline continue. Number two, like the mix shift has actually contributed to earnings. And I think as you well know, you know, wealth has been a huge driver for many of the diversified financial services companies. I expect it con will continue and I’m looking forward to wealth being an even bigger driver for Citi over the next couple years. And then I think there’s a, you know, another element too, which is that the speed and sort of the, the facility that management has in toggling between different types of business for different parts of the cycle has significantly improved relative to how people think about banks 15 years ago. So we were talking about valuations earlier and you know, financial services and kind of banks more specifically kind of dragged down overall market multiples when they were a huge part of the market cap for the US large cap indices in the past.

00:53:39 [Speaker Changed] So let’s talk a little bit about soft data. It’s kind of been negative when we’re talking about sentiment and things like that. This really hasn’t translated into the hard data yet. Tell us what you’re looking at in that space.

00:53:54 [Speaker Changed] Yeah, of course. I mean, I’m shaking my head as you say that ’cause it’s absolutely right. The soft data into hard data in a normal period, you know, gets translated in in over inconsistent time period. So there’s not like a map that says like, hey, the soft data does x and then three quarters later or one month later it translates into something in the market or some other hard data and economic activity. So it’s always a bit of an art interpreting the soft data into the hard data. And yet it’s really important to, to pay attention because it may impact the marginal decision. Right now the soft data has went from catastrophic post the April 2nd to tariff announcements to really awful, to maybe a hair better, but still pretty bummed out. And as we’ve talked about, the economic data has stayed somewhat resilient. That doesn’t mean that the economic data will never show weakness. And again, I’m expecting some soft pockets throughout the second half of the year. Not recessionary, but kind of like sub 2% sub one point half percent growth. I think we should buckle down for, and that’s where I expect more durable earning stories. Secular growth stories will outperform the rest of the market.

00:55:06 [Speaker Changed] So it sounds like there are a couple of catalysts in the pipeline and you’re just waiting to see which direction the majority of these go. Tell us a little bit about what you see is upside and downsized.

00:55:18 [Speaker Changed] Catalysts. Okay. So around tariffs, any given day that we’d be having this discussion, there would be, there’s a new set of news. One thing I do know is that we have a series of deadlines over the course of the summer where people are hoping for some level of resolution. And the way I say talk about this, Barry, is this, is that we may be past peak tar of shock, but we are nowhere close to peak tariff pain. We don’t really know how bad it’s going to be quite yet. And this is why of course companies have been reluctant to significantly change their guidance and their earnings revision ratios have looked, you know, better than some people expected. Here’s what I will say. Even if the reciprocal tariffs don’t hold up and they end up going to the Supreme Court and that’s a decision, the sectoral tariffs which take longer to implement are much stickier and frankly have much long larger.

00:56:09 [Speaker Changed] When you say sectoral like North America Canon?

00:56:12 [Speaker Changed] No, like semis.

00:56:14 [Speaker Changed] Oh, okay. Gotcha. Pharma,

00:56:16 [Speaker Changed] Copper, steel, all of these sectoral tariffs are much stickier and have much greater potential impact than the country to country bilateral reciprocal tariffs.

00:56:28 [Speaker Changed] It, it’s so interesting you mentioned that someone was from a biomedical device company was having a conversation with me. It’s like I don’t understand an iPhone is exempt from China tariffs, but the pacemakers we make that save people’s lives are not, and if we have to relocate this to wherever, to Taiwan, to Vietnam, to Canada, right? The FDA process starts over and it’ll be eight years. So for about half a decade or so, as the the Chinese manufacturer at pacemakers sell off, but before the new ones come online, there’s not gonna be enough pacemakers

00:57:07 [Speaker Changed] Right there. We have a real risk of some of these important raw materials and these important consumer goods and these important medical goods, you know, not being adequately supplied. And so we have to really watch this. So I, so I will say this, that the tariff side is not gonna be resolved over the course of the summer and because it’s gonna bleed out for longer, we may have slower growth, but not catastrophic. But eventually we’ll have some really big sectoral consumer and business impacts.

00:57:36 [Speaker Changed] Huh, really, really interesting. You mentioned some of the news stories and how things are affecting sentiment. How do you see the role of narratives driving market responses? It seems like there are different stories for different asset classes every other week.

00:57:54 [Speaker Changed] Absolutely. The narrative changes. It sometimes it feels like on 30 minute increments, it, you know, it used to be you’d have a couple weeks of a narrative taking hold. I know many people think about this, but the market can really only focus on one thing at a time, one major narrative at a time. You know, and that’s where you end up seeing the bulk of the price movement. For example, is it around tariffs? Is it around inflation data? Is it around fed expectations? Is it around the technology conflict between the US and China? Is it around some geopolitical shock? You know, it’s, but it’s not gonna be all of those things at once, even though I would argue all of those things are happening concurrently. And I think the market has become even more short attention span if we can, you know, personify it here. And as a result, the narratives are shifting very quickly. This is why it’s really important to, when you’re thinking about portfolio construction, to anchor on the right asset class and factor exposures, to layer it with more sort of medium term thematic alpha generating ideas and then offer some ballast to the portfolio, either in less correlated assets or in expressions of the asset class or factor that that has a different duration. So,

00:59:07 [Speaker Changed] So let’s talk about some of the quote unquote less correlated asset classes. There has been a giant move into alternatives, most especially private credit, private equity. What do you see in that space? How is that evolving over the next five to 10 years?

00:59:25 [Speaker Changed] Yeah, let me answer that second part first. I think the evolution of this, this broad bucket of alternatives is gonna be towards more liquid expressions.

00:59:34 [Speaker Changed] More liquid, yes.

00:59:36 [Speaker Changed] Or at least more vehicles that allow for individual investors and, you know, family offices and things like that to invest in these types of vehicles. Right? You don’t have to set it and forget it for like 10 years. I think there’s gonna be a lot of demand just as we’ve seen say traditional mutual fund transfer into ETFs, active ETFs, but be more kind of combined vehicles. The challenge I think is that there’s been so much money, and we know this, we’ve got great data on this chasing this like a small number of deals. And it has become so popular to think about alternatives as an asset class that the returns that some of these strategies have been able to achieve in the past, I think are much more challenged in the future.

01:00:21 [Speaker Changed] Ha Haven’t we seen that in sort of venture capital land? Absolutely. Back in the absolutely the eighties and nineties VC numbers were spectacular. And post.com implosion. Yeah. Not only you have more companies staying private for longer, it just seems like a ton of low hanging fruit were picked, you know, decades ago. Yeah.

01:00:39 [Speaker Changed] The narrative is like 85% of US companies are actually still private. And so it’s really important to have all these vehicles to access them on the equity on the credit side. I hear that. But there’s certain major differences. Of course, if you’re a private company, you may continue to need different types of funding. You don’t have to disclose to your shareholders on a regular basis, of course, that you don’t have to deal with the, the stock price fluctuation and, and all of that, what that might mean for your employees who are paid and, and shares. But it also creates a complicated environment where when you don’t have to disclose, when you don’t have to report, you know, you may make a different set of decisions. Some of that might be good for the long term and some of it may be just like a poor allocation of capital. ’cause no one’s calling you out on it because the capital’s already locked in. So it’s, I would say this 85% of companies that are still private, that the alternative managers are exciting about, about giving you exposure to not all of them are the same quality as the, you know, publicly available, you know, large cap, mega cap companies.

01:01:46 [Speaker Changed] Makes a lot of sense. I want to get to my favorite questions. Okay. But before I do that, I gotta throw you at least one curve ball. You are on the resource council for the Grand Teton National Park Foundation. Yeah. Tell us about that. Does

01:01:59 [Speaker Changed] That sound random to you,

01:02:00 [Speaker Changed] Barry? Yeah, it sounds totally ra I know you’re a former ski bum. I am. So maybe there’s some relationship with that. Yeah, I

01:02:08 [Speaker Changed] Actually split my time between New York City and Jackson Hole. So I spent a lot of time in the Jackson community. I’m super passionate about the conservation and nature programs at Grand Teton National Park. And I’ve been on the Resource council now for about three years. It is a kind of sub-board of the, of the board of the Grand Teton National Park Foundation. And we do some really amazing things. One of the things I’m most passionate about are some of these wildlife programs and the money that we raise specifically for research that benefits some of the biologists in the park and also that, you know, all of the visitors to the park can take advantage of. My favorite thing to do every summer, Barry is the Wolf Watch, which we do some, some days during August, we’ll go up with a biologist to this bluff and we will watch a, a pack that lives in Grand Teton National Park and learn all about wolf habitats behaviors and changes in their patterns.

01:03:04 [Speaker Changed] So, so this is part of the National Park system, but yet there’s a private foundation that helps raise assets and manage resources for the park. Tell us a little bit about that

01:03:15 [Speaker Changed] Structure. Yeah, actually, almost all the national parks have friends groups. And this Grant Teton National Park Foundation is the friends group for Grand Teton National Park. We are a very large and successful one and we’ve really helped to partner with the park on everything from like visitor centers to, you know, accessible options to the, to rivers, to redoing the trail system, to sponsoring some of the biologists, et cetera. The park is run by the park, but the superintendent and the CEO Grant Teton National Park Foundation are close partners. And I like to think, yeah, we’re the best friends group out there.

01:03:47 [Speaker Changed] Huh, really, really quite fascinating. Let’s jump to our favorite questions ’cause I only, I know I only have you for a few more moments. We’ll, we’ll make this our speed round. Starting with what’s keeping you entertained these days? What are you watching or listening to?

01:04:03 [Speaker Changed] Okay, so I don’t watch television at all very infrequently.

01:04:07 [Speaker Changed] No Netflix, no prime, no Apple tv, none of that.

01:04:10 [Speaker Changed] It’s not really my jam. Wow,

01:04:12 [Speaker Changed] That’s really

01:04:13 [Speaker Changed] Interesting. Yeah, it’s not really my jam. I do watch like things, sometimes a news magazine or whatever, but for the most part I’m just an avid reader and I like to spend my time when I’m not working, reading, playing sports, listening to music, and I’m an amateur artist, so I’ve been watching screens after being in front of screens all day long is unappealing to me.

01:04:35 [Speaker Changed] Can I tell you that sounds shockingly healthy.

01:04:39 [Speaker Changed] Yeah. I try to be shockingly healthy. I also try to put my devices down and be focused on other things because I get enough screen time during the day.

01:04:46 [Speaker Changed] I, I totally get it. Tell us about your mentors who helped shape your career.

01:04:52 [Speaker Changed] I don’t know that I had a lot of official mentors. I will tell you, I had more peer mentors, if that makes sense. You know, growing up in the business, I, I was often the only woman in the room, or the only woman on the investment committee. And I built really strong peer relationships with other investors of similar levels around the street. And there are a lot of people who’ve helped to influence my way of thinking or have challenged me. But yeah, I mean, I try and be a mentor to as many, especially young women as I can in the business since I didn’t have that available to me at the time. But I wish I had a long list of mentors, but I would say it’s, it’s more my peer group that I’ve really linked arms with and grown with that I think of as kind of playing that role for me in my career.

01:05:37 [Speaker Changed] Huh, interesting. So you mentioned you read a lot. Let’s talk about books. Yeah. What are some of your favorites? What are you reading right now?

01:05:44 [Speaker Changed] Okay. I’m a giant sci-fi in fantasy nerd.

01:05:47 [Speaker Changed] Oh boy. Were you talking to the right person?

01:05:49 [Speaker Changed] I mean, so on this theme of not watching screens after I work, I like to really escape, like deep in escape after a long day of staring at numbers and analyzing, you know, economics. So here’s what I will say. I am in an amazing series right now, the Murder Bot series by Martha Wells. I know it’s been made into a series. I will not watch it because it will ruin the entire vision.

01:06:15 [Speaker Changed] It’s on Apple tv. It’s gotten mixed reviews so far. Yeah, so far. But I have that in my queue, the first murder box.

01:06:22 [Speaker Changed] Oh, it’s so good. It’s amazing. And you know, thinking about this intersection between bots and AI and the future, and there’s a lot of inner dialogue in there that I don’t think will translate well into a series. But anyway, neither here nor there. So I love to read that before I, I’m on book six now. Before I started that I read the latest from Town of French, which is called the Searcher and, and that and the Hunters two books together, it takes place in Ireland. She’s one of my favorite contemporary fiction authors. It’s like, these are mysteries. And so I love that. And yeah, I pretty much gobble up anything that will make it onto the Hugo or Nebula shortlist. Right. And try and geek out as much as possible.

01:07:05 [Speaker Changed] I had no idea you were a geek. Any non-fiction that that crosses your transom?

01:07:10 [Speaker Changed] Well, the one that’s really kind of stood out to me, and it was recommended by a former colleague of mine from BlackRock is 4,000 weeks.

01:07:17 [Speaker Changed] So good.

01:07:18 [Speaker Changed] So good. And as someone who’s tried to optimize my life many times in the past, but have had a couple he health setbacks and things like that, this was a great reminder that getting through the to to-do list is not the goal.

01:07:31 [Speaker Changed] Right. Oliver, Oliver Burke, something like that.

01:07:34 [Speaker Changed] Yeah.

01:07:34 [Speaker Changed] The, the line that I remember from that book was 4,000 weeks is about 80 years is human lifespan. Yeah. Human life is insultingly brief. Yes. And that phrase just stood out.

01:07:48 [Speaker Changed] Yeah. And this idea that we are all, every day approaching our death is actually empowering. Yes. Instead of discouraging. If you know that you don’t have infant time, you make better decisions. Frankly,

01:08:02 [Speaker Changed] Scarcity is an important economic thesis.

01:08:05 [Speaker Changed] Absolutely. But you cut out the stuff that’s not important and you focus on the things and the people and the experiences that are, and anyway, I love this book.

01:08:15 [Speaker Changed] Yeah, no, I totally agree. Final two questions. Yeah. What sort of advice would you give to a recent college grad interested in a career of, normally I would say whatever the person’s specific specialty is, but you’ve done so much across consulting and strategy and buy side and sell side and hedge funds and portfolio management, and now chief investment strategy. Someone interested in just finance or wealth management.

01:08:44 [Speaker Changed] Yeah. I would say the most important thing is to keep an open mind. One of the most frustrating things, you know, young graduates and even young graduates from business school or or other graduate programs, is that they have like a path in mind. You know, in three or five years I expect to be here in 10 years. And I say keep an open mind because there’s so much disruption and so much change across these industries. You can’t have a mapped out plan. Your goal is to be a sponge and to learn and learn and learn, and also to be patient. Honestly, Barry, I’d say this a lot because you know, you get some like really smart 23, 24, 20 8-year-old who you know, wants to find out what’s over the next hill. And I wanna remind them, you know, if the actuarial tables are even somewhat right, they have 70 more years of life ahead of them. I think that’s right. And they don’t need to rush. They can enjoy the moment of learning, enjoy the experience, and understanding that not just, they’ll have the opportunity to pivot. They’ll have the mandate to pivot. As you know, industries get disrupted and technology evolves. Huh.

01:09:43 [Speaker Changed] Fascinating. And our final question. Yeah. What is it that you know about the world of investing today? You wish you knew 25, 30 years ago when you were first getting started?

01:09:54 [Speaker Changed] I thought there was a more systematic way to approach investing when I first started, you know, close to three decades ago. And now I understand that true investing is both art and science. Maybe that’s the reason why I think I’ll stay in this business for the rest of my life because I’m constantly intellectually challenged to not get frustrated if a model doesn’t work out. In fact, sometimes the process of going through creating a model or a piece of analysis or going down a rabbit hole in research that doesn’t yield anything this year may actually be really helpful for me in three years, or help to reframe my thought process. So understanding that it’s not perfect and that it’s art and science.

01:10:33 [Speaker Changed] Huh. Really, really interesting. Thanks Kate for being so generous with your time. We have been speaking with Kate Moore. She’s the Chief investment officer at Wealth, helping to oversee over a trillion dollars in assets. If you enjoy this conversation, well check out any of the 540 or so we’ve done over the past 11 years. You can find those at iTunes, Spotify, Bloomberg, YouTube, wherever you find your favorite podcasts. And be sure and check out my new book, how Not to Invest the ideas, numbers, and behaviors that destroy Wealth and how to avoid them, how not to invest wherever you find your favorite books. I would be remiss if I did not thank the Crack team that helps put these conversations together each week. Steve Gonzalez is my audio engineer, Anna Lucas, my producer Sean Russo is my researcher. Sage Bauman is the head of podcasts here at Bloomberg. I’m Barry Riol. You’ve been listening to Masters in Business on Bloomberg Radio.

~~~