The transcript from this week’s, MiB: Liz Ann Sonders, Chief Investment Strategist at Charles Schwab, is below.

You can stream and download our full conversation, including any podcast extras, on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, and Bloomberg. All of our earlier podcasts on your favorite pod hosts can be found here.

~~~

This is Masters in business with Barry Ritholtz on Bloomberg Radio

This week on the podcast. Strap yourself in for another great one. Liz Ann Sonders, chief Investment strategist at Schwab, helping to manage $11 trillion in client assets. What a fascinating career she’s had. She’s been on all of the best of lists. She’s just really insightful. What she does is really kind of unique. She combines top down market analysis with looking at everything from sentiment to economic data to fund flows, to really what the clients of Schwab are, are doing. I know Liz for almost 25 years. Every time I speak with her, it’s always great. This is another conversation that is all also fabulous. With no further ado my discussion with Liz Ann Saunders,

Liz Ann Sonders: Always great to see you…

Barry Ritholtz: I know it’s always, I always have so much, I’ve 00:01:11 [Speaker Changed] Known each other for a long time,

Liz Ann Sonders: A long time. It’s always so much fun chatting with you. I wanna talk about what you’re doing with the podcast and what you’re doing at Schwab, but I have to start with a little bit of your background. Undergraduate economics and poli sci at Delaware, MBA in finance from Fordham,

Barry Ritholtz: At the time you went there, was it called Gabelli?

Liz Ann Sonders: No, it was not.

Barry Ritholtz: It’s now called the Gabelli School of School Business. Was the career plan always Wall Street?

Liz Ann Sonders: No, I honestly, I, I think if you brought me back to my college days and asked, what is your career plan? If I was honest, I probably would’ve said not quite sure yet. I, the, the decision to do a double major there was, to keep it very open and broad. All I knew was that I wanted to live and work in New York City. So got out of undergrad, pounded the pavement in New York, but, but across the spectrum of industries, not all Wall Street, I, I interviewed at a sports marketing firm and an ad agency, and I had two interviews in a row at Zweig. Avatar did a lot of research on the company, which by the way, this was in 1986. So doing research on a company meant going to the library, pulling up a microfiche machine, actually cranking the handle I recall, and look at newspaper clippings and was fascinated by Marty Sweig, the, the co-founder and enjoyed the interview process, liked the people with whom I met, and I don’t know, a little voice just said this, this seems to make sense. And

Barry Ritholtz: I recall reading a book, Marty’s Zweig wrote, I wanna say in the late nineties, when I was on a trading desk, Winning on Wall Street,

Liz Ann Sonders: Late eighties,

Barry Ritholtz: Well, I got his book when I started around the time of the Netscape, IPO.

Liz Ann Sonders: That’s when I, he, he did, you know, newer versions. He did updated versions, but I think so…

Barry Ritholtz: Whatever that version was in ninety six, ninety seven. And I vividly recall that. How did you, how did you get the gig with Marty’s wag? What was that like?

Liz Ann Sonders: It, I was a grunt at the outset. I did whatever they needed me to do, but they were a firm that believed in promoting from within and educating their young people. So I saw that as an opportunity. They, they paid for grad school a hundred percent. So I made the easy financial decision to do that at night while still learning a living and having my education paid for. And so many things that I learned from Marty, I could consider him the, the first mentor, whether he realized it or, or not.

Barry Ritholtz: People, by the way, people don’t realize, especially the generation that came of age in 2000, what a legend he was.

Liz Ann Sonders: Unbelievable legend.

Barry Ritholtz: I think at one point in time he owned the, the most expensive apartment in the United States. Is is that true?

Liz Ann Sonders: Yes. It was the top three floors of the Pierre, which is now owned by the Commerce Secretary.

Barry Ritholtz: That’s amazing. And he was always the answer to, “Hey, do any of these technicians make any money?” And the answer was, yeah, look at Marty Zweig. I mean, for, for the younger folks, go look up Marty Zweig. He was absolutely a legend. I remember him from my early days, because he was on Rukeyser.

Liz Ann Sonders: He was one of the originals on, on the original Wall Street Week.

Barry Ritholtz: Yep. I mean, back in the day when all of financial media was an hour, that was television a week. Not even

Liz Ann Sonders: Was a half hour. That’s 8:30 PM Friday nights. That’s right. On PBS produced by Maryland Public Television. That’s right. And Marty was not only one of the original panelists, he was, I think, the original elf as, as Lou used to describe them,

Barry Ritholtz: The people who came back on a regular basis?

Liz Ann Sonders: And that’s another thing that intrigued me about joining the firm, is I remember getting a little bit of a, kind of a wink, wink, nod nod from a, an economics professor that I had, not just to me, but to the class. And he made a funny comment about, given that one of the, the jobs that we had as students was to read the Wall Street Journal every day and just keep up on markets and the economy, and that if you had too many late nights at the Stone Balloon, you might wanna just get a really brilliant 30 minute recap by watching Wall Street Week on Friday night before you then go out. So I thought, all right, I’ll see what this Wall Street Week is all about. And so I started watching it before I joined the business, before I started at, at Swg Avatar. And, and then I joined the show in 1997, which was surreal.

Barry Ritholtz: So you were not that far outta school when you started? 00:06:03 [Speaker Changed] Well, I was, yeah, I was 11 years. So since you and I have talked about our first experience together, which was on TV years, first, it was my first TVeExperience, first TV appearance on Kudlow.

Liz Ann Sonders: And I, I, I went on the show as a special guest. So I remember getting the, the little, you know, pink slip from the receptionist that told you who had called. There was voicemail at that time that said Rich de Roth, the producer of Wall Street Week called They’d like You to come on as a guest. And I thought it was somebody playing a prank on me.

Barry Ritholtz: Really?

Liz Ann Sonders: Yeah, until I called and it was legit. And I went on as a, a guest. And then in shortly after that, they asked me to become a regular panelist, and it was a thrill.

Barry Ritholtz: So you were Zweig for a number of years, [13] you end up go 13 years. Wow. That’s a long time.

Liz Ann Sonders: 86 to 99.

Barry Ritholtz: How did you end up at US Trust?

Liz Ann Sonders: So that was kind of funny. I was on the avatar side of this [Zweig Avatar] broad set of companies, which was the institutional money management side. I was a portfolio manager, co-ran stock selection. But I was always much more intrigued by interested in and with a desire to spend more of my time doing top down macro research

Barry Ritholtz: As opposed to bottom up

Liz Ann Sonders: The inner voice said, you don’t really love this that much. And there wasn’t really an opportunity for that. I, I, it wasn’t that I was pigeonholed, but, but it was a growing role as a portfolio manager. So I got recruited over to US Trust to co-run their large cap growth area, which, which put me yet again in that position, but felt like the platform was broader. And my inclusion on the investment policy committee, they actually purposely wanted some top down analysis based on my learnings for working

Barry Ritholtz: Liz For the ultimate large cap growth means here’s the universe, it’s, it’s a hundred of the S&P 500.

Liz Ann Sonders: , and we were a concentrated manager [only owning 30 positions only?] No less than 25 typically, with a four to five year holding period.

Barry Ritholtz: So not a closet indexer, a high active share.

Liz Ann Sonders: But I also didn’t love the pigeonholing aspect of it. Mm. Where, you know, the mantra had to be large cap growth. I, I, I liked thinking bigger picture and thinking about different parts of the market cycle and what works. So 10 months after I joined US, trust, Schwab acquired us Trust.

Barry Ritholtz: That was 2000. And you’ve been with Schwab for a quarter century?

Liz Ann Sonders: Since then for, it’ll be 26 years. Wow. At the beginning of next year. And the, the re when I realized I did indeed wanna be adopted by the new parent company was when Chuck Schwab himself came to New York with our CEO at the time, Dave Patrick, and sat with me and said, we would like to create this role of chief investment strategist, which didn’t exist at Schwab before. This was the beginning of our entree into actually giving advice as opposed to just being a platform for, for traders.

Barry Ritholtz: So, so let, let’s dive into that. So I was gonna ask you what the process was like, but they acquired us trust for the assets and for the platform. You were a bonus that came along with it, right?

Liz Ann Sonders: Well, well, that’s kind of you to say. Well, I mean, they, they did offer me the, the role. It had not existed before.

Barry Ritholtz: That’s a big deal.

Liz Ann Sonders: And I said, yes, please.

Barry Ritholtz: Yeah, absolutely.

Liz Ann Sonders: And the rest is 26 years of history.

Barry Ritholtz: So let, let’s dive into this. What are the, let, let’s take a look at the numbers on the Schwab platform as a custodian or however Schwab is touching a 401k. How many trillions of dollars are on that platform?

Liz Ann Sonders: 11.23 trillion…

Barry Ritholtz: All right. So keep working at it. You’ll, get somewhere soon…

Liz Ann Sonders: Yeah. That’s trillion with s about a third of the size of the US economy. Wow.

Barry Ritholtz: That’s unbelievable. And at the time, what was Schwab? Schwab in 2000?

Liz Ann Sonders: Oh gosh. One, something like that. It was less than that. Because I remember getting this little…

Barry Ritholtz: Plexiglass plaque?

Liz Ann Sonders: Well, no, it was a, it was a holder for sticky notes and it had a star on it, and it said, you know, 1 trillion in client assets. But that was after the, so that’s acquisition of me.

Barry Ritholtz: So that’s an incredible growth. Schwab really is a platform that are so many things to so many different people. There’s an institutional business, there’s a business. And full disclosure, we custody right at our firm at Schwab, most of our assets are there. So you custody for RIAs and others, self-directed investors, individuals who doesn’t Schwab work with? It’s pretty much everybody in the industry.

Liz Ann Sonders: Well, traditional institutions. So the way we define institutional, when we talk about it and use that term somewhat generically, we’re actually referring to the part of the business that you’re involved with. So independent wealth management firms, RIAs, that, that platform with Schwab via the custody of assets, but a heck of a lot more than just that. So that’s how we defined institutional it of the, and I’m totally using rounded numbers here, but of the 10, of the 11 and a quarter trillion is about evenly divided between individual investors on our platform. Self-directed. Self-directed. And well, not always. Now we have, we have a whole wealth management arm that’s all, that all feeds, not just to the individual investor side of what we do, but to in your world advisor. So advisors on our platform. So that’s about evenly split. And then, then the remainder is workplace services. So stock plans for big companies and managing, managing 4 0 1 Ks. So it’s what we, but we we’re dominated by individual investors, even on the quote institutional side, because most of the advisors on our platform manage money for individuals.

Barry Ritholtz: Hmm. That’s really interesing.

Liz Ann Sonders: So we would consider the advisor our client, but we’re, we’re providing a platform there for them, you guys, to advise for the most part, individual investors.

Barry Ritholtz: And, and I know I’ve told you this story before, but when we launched RWM in 2013, we launched with TD — years later acquired by Schwab. Hold that aside. And we are, were very data driven. We ran a lot of analytics. And every time we didn’t win a prospect when we would go through the list of the reasons, the number one reason is, “Hey, you guys don’t custody with Schwab and my money’s at Schwab and call us if you ever decide to.” Absolutely true. And finally, we all looked at each other, Hey, there’s no reason not to open a second custodian. And so we did. And it caused a flood of new clients and new families joining us because well, well done. But, but the crazy thing is, it’s like I have never seen a financial institution with that much brand loyalty from the audience. From the clients. Because think about it, when you talk to people about Wells Fargo or Citibank or any large financial traditional bank, maybe a little bit at JP Morgan Chase, but for the most part, no one says, oh, “I don’t want to be with you. You are not affiliated with, I’m making up stuff. KeyBank.” But we just heard it so many times. It’s like, all right, you only have to hit me in the head so many times before I realized there’s a, there’s an issue here.

Liz Ann Sonders: The, the power of our reputation is really extraordinary. And, Schwab dates back, you know, about 53 years. Wow. 54 years. That’s, that’s amazing. Yeah. Seventies. And, you know, Chuck has, has written about the history of Schwab and his history. His most recent book was called Invested. And it was essentially a, a memoir of, of his time in this business. And

Barry Ritholtz: When you say Chuck,

Liz Ann Sonders: Chuck Schwab himself,

Barry Ritholtz: Chuck Schwab, who people used to think wasn’t a real guy.

Liz Ann Sonders: No, it’s a real guy. The guy in the commercials is him.

Barry Ritholtz: And he’s still up and about You were telling me he was, he’s just won a golf tournament at 88.

Liz Ann Sonders: Yeah. Last year he won the Nantucket Golf Club. That’s unbelievable. Member, member at 87. And he almost won it again this year at at 88. So regularly shoots below his age, still a very active chair of the board. And but the, the, the culture that he has imbued in in Schwab is really second to none. And, you know, our, our sort of corporate for, for lack of a better word, tagline is through client size. And he has fostered this live, eat and breathe. Everything you do has to be from the perspective of of clients.

Barry Ritholtz: So you are really the perfect person to ask a question. And I’ll ask it specifically about Schwab, but it’s obviously true about the entire industry. You’ve witnessed a shift from a lot of self-directed investors over to the advisor driven side. What has that process been like at Schwab?

Liz Ann Sonders: So it’s not talking about trillions of dollars, right? Not just the advisor side, but investors at Schwab who, who want guidance, who want advice, whether it’s through advisors on our platform or directly with us on our private client side of the, the business. And it’s just the natural evolution of Schwab moving decades ago from a platform for the self-directed to a behemoth that actually provides that guidance and advice now, both directly through certain channels and indirectly through the advisor channel.

Barry Ritholtz: So true or false? And, and I love this question ’cause so many people doubt it. We are today in a golden age for investing for individuals. How do you, how do you answer that?

Liz Ann Sonders: Can I say yes? Yeah,

Barry Ritholtz: True.

Liz Ann Sonders: Just yes. No, I didn’t say true. I said yes, yes.

Barry Ritholtz: its a Golden age of investing for me.

Liz Ann Sonders: Well, I think it’s both true and false depending on how you define,

Barry Ritholtz: Okay. Explain Golden age of investing

Barry Ritholtz: Liz Ann Sonders:. I think we are, as it relates to individual investors that understand that discipline is such an important part of the process that they don’t think of getting get out as investing strategies. I, I fully agree that those are really gambling on moments in time. You wrote about it brilliantly in Well, thank you. In your book, the emotional side. Right. And so I think it’s true in the sense that a lot of those more seasoned investors that take that disciplined approach are, are more equipped now and have more access to information and guidance and when used in the right way has been to the great benefit of their success. But then you have retail traders, which I’m not here to say that they’re, you know, the ultimate contrarian indicator, but I think the perspective there is one of very short time horizons. The, you know, by the dip mentality, which, you know, to their credit,

Barry Ritholtz: That works in a bull market. It works in painful bull market, very painful in a bear market.

Liz Ann Sonders: But a lot of the, you know, younger retail trader that was born out of the pandemic era, it’s not that they have blinders on to the long term or the big picture, but they’ve been, they’ve been, I guess so far, anyway, to your point, properly schooled by virtue of, by the tip has worked. But I’m, I’m starting to get some anecdotal evidence that there, I, I’m not sure that there is a full understanding of what a market cycle actually looks like and that there is downside. So I, I think there, there’s more bifurcation and there’s a wider spread in terms of, of how investors are approaching the market or how traders are approaching the market. And they, they, they’re not in conflict, but they’re kind of at different ends of the spectrum from a what works, what doesn’t work, what are the benefits of taking a long-term approach, having those disciplines as opposed to just, you know, FOMO I’m in and, you know, buy every dip.

Barry Ritholtz: Think about everybody who was born in the 1990s. By the time they come out of college post-financial crisis, they’ve pretty much only known right? One of the greatest rampaging bull markets in history.

Liz Ann Sonders: And, and COVID was, was brutal from an economic three months and market perspective, right? But for, it was five weeks in the case of the market, right?

Barry Ritholtz: Mid February To March,

Liz Ann Sonders: and it was two months in the case of the recession. Right. So

Barry Ritholtz: Although people still didn’t believe it throughout that summer, as, as from the March, 2020 lows till the end of the year, I think the S&P 500 was up 69%. And people fought it the whole way because their personal experience didn’t jive with what they were seeing.

Liz Ann Sonders: Right, exactly. Exactly.

Barry Ritholtz: In inequities, which, which is fascinating. So Schwab created the market strategist role for you, what does it mean being a market strategist? How does that differ from either a PM on the equity side or an economist more broadly?

Liz Ann Sonders: Well, it, it’s certainly differentiated from a PM in that I am not, I’m not picking stocks. I’m not a trader. I don’t analyze individual stocks. So it’s, it’s purely top down

00:20:49 [Speaker Changed] In top down meaning markets economy. Yes. Do you look at sectors? Do you look at fixed income? What

00:20:56 [Speaker Changed] Comes into that? So we have my, my colleague and co-host on our on investment podcast is Kathy Jones. So she’s my counterpart on the fixed income side. She’s our chief fixed income strategist. And I, I say often it sounds like it’s jokingly, but it’s actually quite serious that I was thrilled when we brought Kathy on. ’cause then I was able to stop pretending like I was a deep dive expert in the fixed income side of things. My, my background is on the equity side of things, but what’s unique, I think about this role as it is, as it has existed in the almost 26 years that, that I’ve been at Schwab and have been in this role, is it, it blends the market analysis with the economic analysis. So we don’t have these distinct roles of chief economists and chief investment strategist. And that was always pleasing to me because I, I’m, I, I’m not sure I would either be as effective or enjoy what I do as much if I had to have my market views beholden to economic views that were completely distinct.

00:22:03 I think having that, that overlap and analysis has been a benefit. I also, because our investor base are almost all individual investors, that’s a very different audience that if you’re one of the big investment banking research wirehouse firms, a good chunk of your client base that is, that is a consumer of strategist work being institutions, I think it’s a very different animal in terms of what is valuable, what makes sense. And maybe importantly, again, in keeping with your book, you know, thinking about not just what matters, but what doesn’t matter, what shouldn’t matter. And I, I remember one of the first things that, that Chuck talked to me about 25 years ago was him not being a believer in the whole year end price target, which was music to my ears. Because I think particularly for individual investors, there’s really not that much practical value to that. It’s sort of one point in time every strategist has to adjust those forecasts constantly. It doesn’t tell you about how to manage through market cycles. It’s just one end point to one end point. And so that is certainly one of the differentiators as well, in addition to having that blended market analysis and economic analysis role, not sort of falling into the trap of the way strategists get pitted against one another.

00:23:31 [Speaker Changed] I love that you call it a trap because it’s easy to see what happens when people make a forecast like that and then they tend to marry it regardless of what data comes along. I think it was Ned Davis’ book was called Being Right or Making Money, and he explained how frequently people would just get so hung up on admitting error, right? That they would stay that’s right in the wrong position, the wrong posture, the wrong holdings, rather than admit they were wrong and adjust to whatever

00:24:06 [Speaker Changed] The data is. Yeah. And the trend, you know, one of Marty Zweig was well known for quite a, quite a bit, but you know, he coined the term Don’t Fight the Fed, but he also was known for saying the trend is your friend. And so staying in gear requires constant thinking and rethinking. In fact, I always use as an example of the perils of the year-end price target. If a strategist at the beginning of 1987 basically said the market’s gonna close pretty flat relative to where it ended 1986 by the end of the year, they were right from a point to point, however, to suggest that the market was just boring and flat all year.

00:24:48 [Speaker Changed] So there was that little hiccup in October,

00:24:50 [Speaker Changed] It was just a tiny littles hiccup.

00:24:51 [Speaker Changed] When,

00:24:52 [Speaker Changed] When was the 87 crash? That was Eptember 19th? Yeah, it was September. No, October 19th. October 19th. But there were, you know, there were warning signs and here can I tell you another funny Sure. Early story. So I started in the summer of 86 and as, and we were Marty’s side of the business, which was mutual funds, which was the Wena hedge fund, which is still ongoing onto the leadership of Joe Mena. We would be generically thought of as market timers. We were tactical asset allocators on the avatar institutional side, much more traditional market timing on the Zweig side, particularly the hedge fund. And coming into 87, we were over the cross of strategies, cross strategies were essentially fully invested, but started to get much more pessimistic about the market. In August,

00:25:43 [Speaker Changed] You had a huge run up, huge

00:25:45 [Speaker Changed] Run

00:25:45 [Speaker Changed] Up up until October, August, what was it like 30, 40%? Some crazy,

00:25:49 [Speaker Changed] I think it was more than 40 really? And so we started to adjust allocations down more extreme on the hedge fund side where Marty went, I, I think to anally a net short position

00:26:02 [Speaker Changed] And famously disgusted on Ru Kaiser

00:26:05 [Speaker Changed] The Friday night right before the crash he was on, you can YouTube it now. Yep, yep. And Lou asked him, or or made a comment, he said, Marty, you seem particularly bearish. And, and Marty was seen as this perma bear. Oh really? He was just, but he wasn’t,

00:26:24 [Speaker Changed] I know I don think of him in

00:26:25 [Speaker Changed] That way. He was just, he always was a nervous, he always had a little bit of that, that angst and that humble risk

00:26:30 [Speaker Changed] Aware.

00:26:31 [Speaker Changed] So he would at times be nervous when his view on the market was very bullish. But, so then Lou concluded the question with, do you think we have a bear market ahead of us? And Marty said, well, no, I think it’s more likely to be a crash. And I,

00:26:50 [Speaker Changed] That was Friday night, pretty

00:26:51 [Speaker Changed] Much it could happen any day. And then Monday, and then he not only said that, but then he laid out and I think it could be really ugly. But then I think we, we immediately rally off the low, but then we probably retest the low before we take off again. So here I am, less than a year in the business, we had gone from being almost fully invested in equities down to, I don’t know, 20 or 25% invested in equities. Right. Right before the crash. So the little voice in my head is thinking, what’s the big deal? Why is everybody freaking out? You just figure out before the crash that there’s going to be a crash. You move money out, right? And then you take it back in advantage of cheaper price. You put it back in easy, easy

00:27:34 [Speaker Changed] Peasy pie. Right? Right.

00:27:36 [Speaker Changed] Little did I know.

00:27:37 [Speaker Changed] And, and to just reflect how accurate zoi was, Monday down 22%, a rally that failed the next day. You didn’t quite get back down to the same

00:27:48 [Speaker Changed] Lows. You didn’t fully retest, but, but it

00:27:50 [Speaker Changed] Was pretty ugly again. But you came, you know, 22% in a day is kind excessive. 23%. 20, 22 8. If I, if

00:27:57 [Speaker Changed] All right, I’m rounding. Okay. Yes.

00:27:59 [Speaker Changed] And, and double check those numbers. I could be wrong, but, you know, portfolio insurance was a big part of that. Probably made what was a 10% correction more than double. So maybe that’s why you didn’t retest. And then it was off to the races, the race back to break even

00:28:15 [Speaker Changed] For the year. Right. And, and we had started buying after the, after the crash. So ended the year with just off the charts performance. And again, you know, naive young me is thinking, I don’t know why everybody’s freaking out, out so much. Why

00:28:28 [Speaker Changed] Are these people talking about how difficult this, it’s hard. So the obvious question, how significant was Marty to shaping your framework for understanding markets?

00:28:39 [Speaker Changed] Oh, extraordinarily impactful. Because I, I think the thing that resonated with me the most, and you wrote about it in your book, and it’s the likes of the Sir John Templeton quote about bull markets are born in pessimism, the grown skepticism, mature and optimism die on euphoria. I think that’s such a brilliant way to describe a market cycle, in part because the only terms used in there have to do with emotions. Exactly. There’s nothing in that line about market cycles that has anything to do with what we all obsess about on a day-to-day basis. Monetary policy, fiscal policy, what the next inflation report is going to be, even earnings and, and valuation. And Marty understood that too. And so much of the work that he did was steeped in that sentiment analysis. I,

00:29:20 [Speaker Changed] I love that you brought that up because I, I, so I took the technical analysis training course with Ralph Por, and I don’t really think of myself as a technician, but I certainly wouldn’t buy anything without looking at a chart. Right. It has to be a component, right? I don’t, I don’t need to see an analyst research report, but I have to at least get a sense of is it trend up? Is the trend down? Has this been going sideways for years? And the best technicians I know have always brought in behavioral economics Yes. And sentiment before we called it behavioral finances. Absolutely. And Marty certainly was one of those

00:29:56 [Speaker Changed] People. Absolutely. And so my my maybe sort of added focus on the emotional side, the sentiment side of the market very much was born out of my time working for, for Marty. And I, I still think it’s extraordinarily important. And, and one of the, the messages we always impart to our investors is ideally you don’t figure out the hard way whether there’s a wider or narrow gap between your financial risk tolerance and your emotional risk tolerance. Right? ’cause those two at times can be completely different. And I always describe financial risk tolerance as kind of what’s on the proverbial paper, right? What

00:30:36 [Speaker Changed] Can you,

00:30:36 [Speaker Changed] Your time horizon in, would you need income? What is this money for? Is it for retirement diversification, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. But if you are going to, you know, panic and sell everything at the first bear market level declines in your portfolio, you’re maybe not as risk tolerant investors as you, you thought. And it’s, it’s just the vast majority of mistakes that we see. Extreme mistakes purely driven by emotion.

00:31:04 [Speaker Changed] It, you know, there’s a line I remember from when I was on a trading desk that I didn’t really understand then, but it sums up what you, that gap between your financial risk tolerance and your emotional risk tolerance, which is figure out who you are because Wall Street is an expensive place to learn. Exactly right. You don’t know who you are. You don’t know what your emotional pain allowance is. You don’t wanna panic out the word capitulation technically means surrender. So you go to a, a March oh nine, that capitulation meant people just couldn’t take the paint anymore. Make it stop. Just get me out of everything. And that’s how bottoms

00:31:44 [Speaker Changed] Are found. Can I share the March oh nine? Oh

00:31:46 [Speaker Changed] We were talking about? Yes. I, we were talking about 00:31:48 [Speaker Changed] I would love to hear that, but it, we didn’t have microphones in front of us. That’s right. So it was, let’s go back to March 6th, 2009. So I lived in Darien, Connecticut for 22 years. We raised our kids in Darien, and it’s one of the, the hotbeds of Wall Street, in fact, bedroom

00:32:08 [Speaker Changed] Community, short commute to the

00:32:09 [Speaker Changed] City, short commute to the city. Our town made the cover of business week in 2008, the latter part of 2008, as the town most impacted by the financial crisis in the country. And they did it based on the percentage of the working population that worked either on Wall Street in some capacity or in real estate. And so it was, I was surrounded by Wall Street people, not a lot of Wall Street women. It was also a town where most of the, the women who were raising kids were, were stay at home. So I was always steeped in conversation about the markets. And in the role that I had, I would always get peppered with questions. So my husband and I are at a dinner party in Dairy End. It was toward the end dinner and dessert had served maybe about a quarter of the people had left a smaller crowd just sitting around chatting. And the host of the party who was at that time, a 30 plus year veteran of Wall Street, said, Lizanne, I must say I I don’t envy you right now. And he was a bit dramatic, and he kind of paused for effect. And I said, oh, what do you mean? And he said, well, I really think that there’s no chance that the stock market ever gets to another high. I think there’s a decent chance that retail investors will never buy again. Wait, never, never,

00:33:30 [Speaker Changed] Never. Just done.

00:33:31 [Speaker Changed] Which makes me question the, the viability of a company like Schwab. And so I don’t even remember what I said. I I think I did some generic version. Well, I beg to differ, but I, I didn’t, I was also ready to leave. You know, I I, I I, I like a nine handle on my bedtime. So if it’s 1130, I’m like, okay, chop, chop. So I, I just, I, I wanted to end the night. We get in the car unprompted, I, and I haven’t had to embellish a story at all before. My husband puts a key in the car. He looked to me, he said, did you hear it? And I said, the bell ringing. Yep. He said, I knew you were thinking that. So I called my friend the next morning and I said, I am working on a report. And all of my research reports, written research reports, I use rock song titles, right. I’m a rock chick from way back. So I said, I am working on a report that I want a title. Here comes the sun. Can I share the anecdote? No

00:34:27 [Speaker Changed] Name, just the no

00:34:28 [Speaker Changed] Anecdote. I said, I’m not gonna mention name. He said, sure, I think you’re gonna regret it. Every time I see him, he does like the fist to the forehead. Like, oh my gosh. And that was when the last person is standing has gone down. Right. That is, and I think that’s inter what’s interesting about sene is we know sentiment at extremes serves as a contrarian indicator.

00:34:51 [Speaker Changed] Right. Most of the time you could pretty much ignore that middle

00:34:54 [Speaker Changed] Range without, without anything resembling precise timing. That said, as we all learned in the late 1990s, extremely optimistic sentiment can last for a really long time. Right. You know, Greenspan made as a

rational exuberance comment in 96,

00:35:08 [Speaker Changed] December 96.

00:35:08 [Speaker Changed] That’s right. And it wasn’t until, you know, three plus

years later that the market topped out

00:35:12 [Speaker Changed] March, 2000, almost four years.

00:35:14 [Speaker Changed] That said, when sentiment gets to such an extreme of despair, it’s not a precise contrarian timing, but there’s a narrower window. Pay

00:35:24 [Speaker Changed] Attention.

00:35:24 [Speaker Changed] Yes. Pay more attention to extremes of despair than you do extremes of enthusiasm, because the ladder can last a long

00:35:32 [Speaker Changed] Time. Tops are a process. Yes. Bottoms are a moment. Bottoms are a moment. Exactly. Absolutely. And you know, there are all these old trader cliches and stuff, but they become cliches for a reason. A reason. Absolutely. And, you know, we all experience the world in a very narrow window of 8 billion people on the planet. Our experiences are maybe 10th of a percent of what the rest of the world is experiencing. And so we tend to extrapolate out to the rest of the world. But very often what’s happening in the markets is not a reflecting your personal experience, but after you’ve lived through enough cycles, you start to be able to hear those sort of things. I had a, that was a pure death of equities business we call cover from the late seventies and a year or two later. That was it. It was the next thousand percent route

00:36:28 [Speaker Changed] Market. Yeah,

00:36:29 [Speaker Changed] Absolutely. Amazing story. I

00:36:30 [Speaker Changed] Have one other anecdote that’s an interesting one to think about how emotions come into play was out in Silicon Valley area maybe about a year ago, a little less than a year ago, and heard from a client that he had finally given in to his financial consultant suggestion that he trimmed just back about 10% of his NVIDIA holdings. He was an ex-employee, had a lot just, you know, diversification,

00:36:55 [Speaker Changed] Right? We’re gonna leave some money on the table in order to reduce your drawdowns and

00:36:59 [Speaker Changed] Volatility. And he ended up splitting the difference. He didn’t wanna trim any, he trimmed 5% and then the stock went up by 20 some odd percent in the short term. And he, he was mad at the financial consultant that the stock had gone up. And to his, our financial consultant’s credit said, would you really be happier if the 95% you still own went down 20%?

00:37:22 [Speaker Changed] Listen, in the beginning of this year in video lost, but that’s psychology of its value

00:37:26 [Speaker Changed] That they, he was almost more, and he, to his credit, he said, you know what, that’s the way I should think about it. Was more concerned about the top tick, the bottom tick. Right. I trimmed it. Wasn’t I brilliant because then the stock went down 20%. So it it, our emotions play tricks on us in a lot of different directions.

00:37:43 [Speaker Changed] You, you brought up my book, I try not to talk about it on the show. It was a great book. But the regret minimization chapter Yes. Is all about your role as an individual investor is not to outperform the market, right? Or top tick or bottom tick stocks. It’s, Hey, how can you avoid making decisions that you’re gonna say 10 years later? What an idiot. I was. Right. Just, just as Charlie Munger said, what can you do to be less stupid? Right? And if, you know, we see these portfolios that started out as a million or $2 million, but through either smarts or good Luck or some combination. They had a big slug of Nvidia 10 years ago, and now they have a $20 million portfolio, 18 million of which is Nvidia. Hey, do you really wanna ride this up and down? Yeah. You’ve won 20. Yeah, exactly. Think about what $20 million in long-term investing does for you. Do you really wanna ride this down when it takes one of its regular drawdowns? And what I wanna say, it gave up about a trillion dollars in market cap this year before recovering. But

00:38:50 [Speaker Changed] Can I, can I say something else? Not, and I’m not an analyst, I don’t cover Nvidia, but the whole focus, the Uber focus on the magnificent seven, let’s just use that as an example of a cohort. So the, we’re dealing with cap weighted indexes in the case of the s and p and the, and the nasdaq. And I think one of the messages we impart to individual investors is, don’t feel like you have to have the same concentration as what’s embedded in these cap weighted indexes. That’s an institutional problem. If you’re benchmarked against the s and p on a quarterly basis, right. You are at the mercy of the construction of that index. But as a, an example of how I I describe this, Nvidia is the best performing stock within the Mag seven year to date, but it’s the 47th best performing stock in the s and p 500. Wow. It’s the number one contributor to s and p gains by cap by virtue of the multiplier of the cap size. So there’s 46 stocks in the s and p that have out, that are outperforming Nvidia this year. NVIDIA’s, I think rank number 630 something in the nasdaq. Meaning there’s 630 some odd stocks within the NASDAQ that are outperforming the best performing mag seven. So it’s the concentrate, it’s the contribution that sometimes gets conflated with the performance.

00:40:07 [Speaker Changed] I have a buddy who’s a technician who looks at a ratio of the market cap s and p versus the equal weight s and p. And what we’ve been seeing this year is the equal weight, I’m trying to remember where we are now. I haven’t looked at it recently, but when it’s going up, it’s telling you the big caps are faltering. And when the ratio is going down, it’s telling you the big caps are doing well, unless I’m, I’m doing that backwards. It depends on which one is the numerator, which one is the denominator. But clearly the outsized weight market cap wise is, is Nvidia number one or two behind Microsoft or Apple?

00:40:43 [Speaker Changed] It’s number one right now. But it’s been, you know, meta and alphabet have actually been kind of battling. But, and then also Microsoft, those are the four of the mag seven that are outperforming the s and p year to date. The other three are underperforming. And in fact, a few days ago, ’cause I tracked this on a daily basis, apple was down, I think 7% year to date that was, is its worst year to date performance. And it was the 503rd ranked contributor to the s and p. So the multiplier of cap size works in the other direction if, if you’re an underperformer as well. And a lot of people say, well, what do you mean 503? The s and p has 500 stocks,

00:41:19 [Speaker Changed] A and B shares,

00:41:20 [Speaker Changed] Google,

00:41:21 [Speaker Changed] Berk, Berkshire, you have a few big

00:41:23 [Speaker Changed] Companies like that. So

00:41:24 [Speaker Changed] That’s a great trivia question, how many company, how many stocks are

00:41:27 [Speaker Changed] In? How many stocks are in the s and p 500? And there’s also not 2000 in the Russell 2000

00:41:31 [Speaker Changed] Or the Wilshire 5,000. It’s like 3,400.

00:41:33 [Speaker Changed] Well there yeah, the WIL 5,000 used to be about 8,000 stocks, and now there’s just fewer stocks that are

00:41:39 [Speaker Changed] Publicly traded. Yep, absolutely. Coming up, we continue our conversation with Liz Ann Saunders, market strategist for Schwab, discussing the current environment. I’m Barry Riol, you’re listening to Masters in Business on Bloomberg Radio.

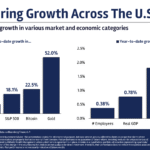

00:42:05 I’m Barry Ritholtz, your listening to Masters in Business on Bloomberg Radio. My extra special guest this week is Liz Ann Saunders. She is the Chief market strategist at Schwab, helping to oversee $11 trillion in change in client assets. So I went back and looked at my notes the last time we had a conversation like this was spring of 2024. It was six months before the election. I don’t think the election surprised many people. Right. It sort of felt like that was inevitable. Maybe that’s a little bit of hindsight bias. How has this year played out since January 20th relative to expectations?

00:42:47 [Speaker Changed] Well, you know, let, let’s focus on not so much the beginning of the year, but the setup going into April 2nd. I think that was a pivotal point because we knew tariffs were coming, but I think there was complacency as to what the announcement would be on April 2nd. An assumption that okay, 10% across the board, tariffs, it’s kind of built into expectations.

00:43:08 [Speaker Changed] You call it complacency. I, I call it a failure of imagination. Yeah. Because afterwards, a

00:43:13 [Speaker Changed] Failure to imagine the Cheesecake Factory menu being held up and reciprocal tariffs of a massive size. Right? Yeah.

00:43:21 [Speaker Changed] Right. Because you think about it, he talked about tariffs. He’s, I called himself tariff man, it’s the most beautiful in the dictionary. None of us imagined that he would just

00:43:31 [Speaker Changed] Overturn the order. And that, and that reciprocity wasn’t about tariffs that other countries had as part of their policy, but reciprocity relative to trade deficits. And the confusion that that brought about, when you think about there are many countries, particularly smaller,

00:43:47 [Speaker Changed] Vietnam is the classic example,

00:43:49 [Speaker Changed] But also, you know, the Madagascar and Bangladesh, right? We’re never going to have a trade surplus. They can’t afford, they buy teen their teeny. And in the case of, you know, a, a place like Madagascar, they produce most of the vanilla in the world that gives them literally and figuratively in industry. And they can’t afford to buy what we export, which is much more value add. So I think that was a big surprise factor.

00:44:13 [Speaker Changed] A math a, it’s effectively a conceptual math error. Yeah.

00:44:17 [Speaker Changed] And of course, running trade deficits. The other side of that is a, a capital account surplus. So we export dollars into the rest of the, the world, right? And those dollars have to be put to work and they get put in treasury

00:44:29 [Speaker Changed] Here, some paper we printed us.

00:44:31 [Speaker Changed] And so I think that became a, a significant concern. I also have been really shocked, Barry, at how the general public doesn’t understand literally who pays the tariffs.

00:44:45 [Speaker Changed] It’s a VAT tax, it’s evaluated tax on consumption’s. 00:44:48 [Speaker Changed] The first time I decided, I was speaking to an audience in Naples, Florida in the spring, that well to do audience. So assuming they have some investment expertise, but we’re not, we’re not deep in the import export business. And I decided, let me just lay out the actual definition of tariffs. I said, notwithstanding the shorthanded headlines of tariffs on China, tariffs on Mexico, fill in the blank. Tariffs are paid by the US company importing the goods. They’re not paid by the targeted country. It is not the case that, as I’ve heard from friends who didn’t understand how this worked, that in order for China to export goods into the United States, China has to pay a tariff to the United States. Barry, do you know how many people came up to me after that event and said, I had no idea. And that’s what’s a little frustrating because there’s still that shorthand. And at times when there are comments made by the administration that, you know, China, again, fill in the blank of the country, paying us more in tariffs. It’s the US company. It’s a tax on US companies. Now, a valid debate is who ultimately bears the cost and is it the exporters that will lower their price to offset the tariff that the US company has to pay? Very little indication that that is happening. And then of course it’s do companies eat it in their profit margins or do they pass it on to

00:46:09 [Speaker Changed] Consumers? But, but either way, either companies are gonna have lower profits, which means the stock market could support a lower PE multiple, or there’s only so many dollars. It’s finite. Right. If, if they’re, so what we saw, we saw this is taking place in three steps in anticipation of the tariffs going into effect. And especially with the 90 day pause on April.

00:46:31 [Speaker Changed] Well, so that was the thing that happened.

00:46:33 [Speaker Changed] So ton of excess import inventory bills

00:46:35 [Speaker Changed] In one week from April 2nd to the intraday low on April 9th. There was sort of a complete about face. So what none of us can do is try to gauge what the next social media post is going to be. Right. There’s been so many fits and starts from a tariff perspective, whether it’s delays, tariffs coming down, exceptions. This has been a, an elongated process. It was certainly wasn’t a moment in time kind of thing. But what we can analyze, especially as a, as a strategist, are the setups. So we already talked about the setup going into April 2nd. Well, the setup shifted very quickly. So you went from complacent sentiment to despairing sentiment. You,

00:47:18 [Speaker Changed] You had a VIX in the low teens that spiked up, spiked to 30, and I want, on the eighth, I wanted to buy. And I’m like, I have no idea what the hell the next tweet is gonna be. Right? Can I really put money in my personal account, put money on at risk that could be destroyed by a

00:47:35 [Speaker Changed] Tweet. But then, then you had the market, technically oversold breath had fully washed out. So then you, that was the attraction was really just incrementally positive news intraday on April 9th off to the races and off to the races, right? But then you had the power of the retail trader and that cohort has become unbelievably power powerful representing somewhere in the 20 to 25% of daily trading volume. And that by the dip mentality was such a fuel for the market. What concerns me a little bit now is if I, I track a lot of the baskets that track like micro baskets of, of stocks. Goldman has a lot of them. UBS has the meme stock basket. You go back to that intraday low on April 9th. And it’s baskets like the memes, non-profitable tech, heavily shorted stocks. That is the perfect example of retail traders kind of powering this market higher. And in the heavily shorted piece of that, it’s also suggestive maybe of retail traders with a little bit of the stick it to the man, which, which drove the initial meme stock CRAs back, back

00:48:36 [Speaker Changed] In 2021 sort of GameStop thing.

00:48:39 [Speaker Changed] Yeah. And it’s, it’s alive and well again, it it, it actually has forced institutions in some cases to cover shorts, which has added to the, the fuel. Now, I think as we think about the setup, we’re arguably back in a similar pre-AP April 2nd, a bit of complacency and which may means some vulnerability to the extent you get some sort of negative

00:49:02 [Speaker Changed] Catalyst. So, so that’s where I wanted to go. Since we’re talking about the current environment. It felt like a lot of savvy companies loaded up on inventory in that 90 day pause front, ran the tariffs and Right. Exactly. And then they were capable until that ran down of not really being affected by tariffs. And then even as the tariffs started to bite, they seem, it seemed like they were eating the increase and not passing it along. But that can only go on for so long. It feels like the next phase is consumers are gonna pick it up.

00:49:38 [Speaker Changed] And to your point, Barry, there, there wasn’t much of that eating it at the early stages because of that inventory build by front running the tariffs and building inventories at a low cost basis, providing some time flexibility around when to make the decision of eating it in the profit margins or passing it on to the consumers. We’re now starting to see attempts to pass on to the consumer. But the, maybe the more interesting thing to consider right now is so much focus on goods that are impacted by tariffs. What’s the rate of inflation in those goods? Trying to gauge the tariff impact on the inflation statistics. But what we’re, we’re also starting to see is demand destruction and switching on the part of consumers. So I think we have to analyze the impact of tariffs in a parallel fashion, not just gauging what the inflation impact is. And you can do that by separating out goods and services within the goods categories of an inflation metric like CPI look at those that are directly impacted by tariffs, not impacted by tariffs, but there’s the demand destruction side of things. So we track the weekly consumer spending data, and if you separate that into tariff impacted categories, that’s where you’re seeing a compression in that spending.

00:50:54 [Speaker Changed] So to be fair, when you look at the US as a 30, $31 trillion economy, when you look at the value of imported, and, and by the way, that economy is much more services than goods oriented. And then you look at the percentage of goods that are imported, it’s a trillion or 2 trillion out of, i, I know it sounds crazy to say, yeah, what’s a trillion, but it’s a trillion out of 30 plus trillion dollars. So the worst case scenario is it, it takes a quarter or half a point outta GDP, but probably doesn’t tip us into a recession. Is that a a fair way to describe that?

00:51:30 [Speaker Changed] Yeah, in and of itself it probably doesn’t. But there’s, you know, the feedback loop that happens if company rate labor where if companies, because they don’t have that ability to pass most of it on to consumers in part because of the demand destruction that I’m talking about, then there’s that eating in profit margins. And then does that feed into the labor market side of things? I think that’s why the Fed did what it did. The risk little insurance, the risk management, the insurance cut to try to stem any weakness in the labor market.

00:51:58 [Speaker Changed] So, so let’s talk about those crosscurrents, since you do both markets and the economy. We’ve had a softening labor market at least the past few months. And then the whole, i, I don’t know if that re statement is precise, but it certainly makes it clear we were too optimistic about the labor market over the past four quarters. Inflation, sort of residual sticky inflation that hasn’t come down to the fed’s 2% target. We can argue about whether that really should be a 3% target. But hold that aside. Yet at the same time we sort see corporate profits continue to grow and markets making new all times highs, which that combination expanding profits all time price highs tends to be bullish historically. How do you navigate all of these positives and negatives? Well,

00:52:49 [Speaker Changed] Here’s one way to to think about the connectivity between the market and the economy. I think it’s very circular right now. Or maybe chicken and egg. And what does make me harken back to the late 1990s as a bit of a comp to the current environment is not so much is it a bubble? And there’s more there. There in the AI world, a

00:53:10 [Speaker Changed] Lot of revenue, a lot of process. There’s

00:53:11 [Speaker Changed] Actual denominator in the valuation equation, which not 00:53:14 [Speaker Changed] The clicks case and eyeballs,

00:53:15 [Speaker Changed] Right? Not clicks and eyeballs. Not every company just adding.com, you know, to the end of their name. But the wealth effect and it’s chicken and egg. And what makes me think back to the late 1990s is in that 99 blow off into the peak in 2000, whether it was valuation metrics like the buffet model, which looks at total market cap of all US stocks as a share of total GDP,

00:53:41 [Speaker Changed] Which is at all time highs now,

00:53:43 [Speaker Changed] Which, and way higher than it was back at the peak in 99 or 2000 at the time, households exposure to equities as a share of their financial assets. Well, at an all time high, significantly higher. So if we remember when the market topped out in March of 2000, and then we started what was a two and a half year bear market, we ended up getting a recession declared in 2001. It was a very mild recession. It was one of the proof points, which for what I always say drives me crazy that people think of recession as traditionally or classically defined as two quarters in a row of GDP. That’s never been the definition right. Of recession. Hundred percent. NBER is, that’s

00:54:21 [Speaker Changed] A pet peeve of mine

00:54:22 [Speaker Changed] As well. It drives me crazy. And in fact, oh, one with the benefit of revisions wasn’t two quarters in a row of negative

00:54:28 [Speaker Changed] GDP. That’s right. Same, same thing in 2022 people were talking about it. Right. The revision, the

00:54:33 [Speaker Changed] Revision took out that one plus quarter

00:54:36 [Speaker Changed] Plus when you have a spike in inflation, it’s not that the economy is contracting, it’s that we back out price increases. Right, exactly. The economy is so hot. Exactly. That inflation makes it look negative, right. It’s not, it’s not a contraction, it’s just a price problem.

00:54:51 [Speaker Changed] But that oh one recession was actually very mild, began

00:54:55 [Speaker Changed] In March. I think it ended in October.

00:54:57 [Speaker Changed] It ended in October, right. Short. It was mild. There were, there was not really a financial system crisis for sure. It wasn’t a credit crunch. I think it was the weakness in the stock market caused the economy to contract because of the wealth effect at the time.

00:55:12 [Speaker Changed] I’m gonna take it just a step further. I have vivid recollections of speaking to people, speaking to clients or other people’s clients in 96, 97, 98, 99, who had been in the market for 15, 20 years. Hey, we want to trade up to an ISA house. Hey, we want to buy a beach house, a lake house, a vacation property. And the person said, I’m, I’m not sure if the market’s gonna go higher from here, but I want to pull half a million outta my account and buy real estate. It’s like, Hey, you’re gonna have that house for the next 25, 30 years, even if the market keeps going higher, who cares? You’re sitting on such profits, why not? And so I kind of got a sense that it wasn’t so much the wealth effect as people had already done the big buys before the market crash, which tends to freeze people in place. Yeah. So I saw a lot of rotation out of equities just because people were sitting on, look, from 82 to 2000, the Dow gained a thousand percent. People were taking a little of the house money off the table and letting less the rest ride. And then the.com implosion, I wanna say 82, 80 3% peaked a TR on, on nasdaq. On the queues. Yeah.

00:56:33 [Speaker Changed] 57% on the s and p, you know,

00:56:35 [Speaker Changed] 80 plus percent. And the Dow held up the best because it was least exposed back then. Right, right. Least exposed that before Microsoft and Intel went

00:56:42 [Speaker Changed] Into Intel and price, weight did not cap, right?

00:56:43 [Speaker Changed] Yeah, that’s right. Yeah. So the

00:56:45 [Speaker Changed] World, so I just think we, and again, it’s a bit circular in that, you know, if and when we get another bear market, we essentially had one this year, just missed it on the s and p

00:56:58 [Speaker Changed] 19%.

00:56:58 [Speaker Changed] Think at the index level. Yeah. But the, here’s, here’s another set of statistics. The average max, the average member, maximum drawdown for the s and p year to date is 24%. Hmm. So the average member has had a bear market. Huh. That’s interesting. The average, average member within the NASDAQs maximum drawdown is 47%. Wow. Now you want

00:57:19 [Speaker Changed] Cap weighted.

00:57:21 [Speaker Changed] Well, the average member, just each individual member. So not cap weight, what was there? No, ’cause it’s individual members, right? You just track what each member maximum drawdown was at any point, and then take an average of that. But here’s the maybe more interesting one. In an environment since the April 9th intraday low, we haven’t had much of any kind of pullback in either the s and p or the nasdaq. But just since that low, in an environment where the s and p hasn’t even had a 2% pullback, the average member within the s and p since the closing low on April 8th, has had a 14% maximum draw down. Hmm. And within the NASDAQ has had a 32% maximum drawdown. Wow. So there’s a lot of rotation and churn under the surface, which you don’t pick up if you’re only focused on the index level, which has that cap bias to it.

00:58:07 [Speaker Changed] Hmm. That’s amazing. So last question before I get to my favorites. We we’re talking about a lot of things that are in the headlines. What do you think investors are not thinking about or talking about, but perhaps should be? What topics, assets, data points, you know, are getting overlooked?

00:58:26 [Speaker Changed] There was one I thought about this morning, and it’s not so much what people aren’t talking about, so I’m gonna answer in a different way. It’s what I hear a lot of people talking about that isn’t quite the right way to think about it. And that is the cash on the sidelines argument. Ugh.

00:58:41 [Speaker Changed] So it’s y hated that, and I’m not a fan either,

00:58:44 [Speaker Changed] But it often, the specificity around that has to do with the amount of money in money market,

00:58:49 [Speaker Changed] Seven point something

00:58:51 [Speaker Changed] Trillion, seven 7 trillion in change. Yeah. And that, that is sitting there as either, if not imminent, but ample fuel that if that money decides to repatriate from money markets into the equity market, boy, we go off to the races.

00:59:06 [Speaker Changed] Didn’t that money mostly come from bonds? It

00:59:08 [Speaker Changed] Did.

00:59:08 [Speaker Changed] You’re getting such low yield and bond. So my,

00:59:11 [Speaker Changed] I think a lot of it’s

00:59:12 [Speaker Changed] Sticky. My Schwab money market account last summer, so we bought a house, a beach property in February last summer. I was getting like 5 3, 5 2 in, in the Schwab, what is it? Snacks. Snacks. I don’t even remember the symbol. I’m like, why do I need to mess around with 10 or 20 year bonds when I’m getting much better?

00:59:31 [Speaker Changed] But here’s the other angle to that. If you think of $7 trillion as some massive fuel for the market, you need to look at it as a ratio relative to the total right market capitalization. And

00:59:45 [Speaker Changed] It’s gone up less than the stock

00:59:47 [Speaker Changed] Market has. It’s, it’s only 12%. The all time low in that, in the history that we have for that data is 11%. To put that in context, in oh 8, 0 9, when money was flying into money markets, because it was fleeing the equity market at the peak money market assets relative to the size of the stock market was more than 60%. Huh.

01:00:11 [Speaker Changed] That’s

01:00:11 [Speaker Changed] Huge. Now we’re only at about 12%. So the math is such that even if all $7 trillion was to leave on mass and go into the equity market as a fuel at 12% of total market cap versus say, you know, 63% of total market cap in oh nine, that’s a very different, not to mention back to our initial point, I think a lot of that money is sticky. That was money that was forced out the risk spectrum into other categories within the fixed income market in order to pick up yield when there was none to be had. So I, I don’t think we should consider that some sidelines cash that is just itching to find its way back into the riskier asset classes.

01:00:52 [Speaker Changed] Someone once debunked the cash on the sideline argument, and it might have even been Marty Sweig in winning on Wall Street by explaining it this way. Hey, I’m gonna buy a million dollars worth of stock. It means I have a million dollars worth of cash, but no stock. I buy a million of the SPY, now I have the SPY. Right? And, and, and they have a million on of cash

01:01:16 [Speaker Changed] For every buyer. There’s a seller. The

01:01:18 [Speaker Changed] The, there’s no cash on the sideline. It just changes hands. It just changes the same dollar amount. So it’s been one of those things that has persisted forever.

01:01:25 [Speaker Changed] And that also the more buyers than sellers. No, no, no, no.

01:01:29 [Speaker Changed] So that you, you are tagging all my, my favorite pet peeves.

01:01:33 [Speaker Changed] I mean, there’s maybe more enthusiasm on the buy side versus the enthusiasm, but there’s no more buyers and sellers or vice versa for every buyer

01:01:41 [Speaker Changed] That’s a seller. But my head trader used to say, there are more buyers and sellers at this level. And now you go up to the nice price next price level where there are matching number of buyers and sellers and the price stabilizes. Right. If a price is going up, okay, at that particular do at at 27 55, there may be more buyers in stock for sale. But at 27 75, then you, you’ve, that’s how you end up with price stability. So yeah. More buyers and sellers. No, no. They’re an equal amount of buyers and sellers. That’s how the other line I love has been trade takes place where there’s a disagreement about value, but an agreement on price. Hmm. And that seems to really Yeah. E explain that. Yeah. All right. I like that one. I have to get you out to, to catch your plane. So I only have you for a limited amount of time. Let’s, let’s speed through our favorite questions. Starting with, tell us about your mentors who help helped shape your career. I’m pretty sure I know the two

01:02:37 [Speaker Changed] Shocker. Marty Zweig. Yeah. Chuck Schwab.

01:02:40 [Speaker Changed] Okay. And

01:02:41 [Speaker Changed] In the world

01:02:41 [Speaker Changed] Of, by the way, not not too shabby

01:02:43 [Speaker Changed] Mentors. Right. Not too shabby mentors. Yeah. Boy was I lucky. And I will say in the world of media, another name we’ve already touched on, Louis Ru Kaiser. One of the best pieces of advice he gave me was, was one, I was on the show for the first time as a guest, and he was saying hello to me for the first time, welcomed me onto the show. This was off camera. And he asked me whether my parents were still alive and whether they were finance people. And I said, Nope, far from it. He said, okay, when you come out here and do the interview with me, get them to understand what you’re talking about. And that was such a, a moment of, okay, get people to understand what you’re talking

01:03:19 [Speaker Changed] About. That’s so funny. You say that. Great advice. You say that my mom was a real estate agent. My wife is an art teacher. And it’s always make them understand it. Yeah. Right. Don’t, don’t don’t clutter it up with jargon. That’s right. Make it hundred percent. That’s interesting that it was, it was Ru Kai who said that. Let’s talk about books. I mentioned Wags winning on Wall Street. What are some of your favorites? What are you reading right

01:03:40 [Speaker Changed] Now? So, my favorite, so I’m not reading a book right

now. I, I must say I don’t have a lot of time. I read constantly. I drink from a

fire hose of information, but it tends to be, you know, like reports

01:03:51 [Speaker Changed] And

01:03:52 [Speaker Changed] Analysis reports and deep dive fed research. And, but my favorite book of all time, and it is market related, is reminiscences of a Stock Operator. Sure. Absolute favorite. I I tell young people to buy it all the time. It still resonates today. And you

01:04:07 [Speaker Changed] Substitute AI for railroads and telegraphs. Exactly. And it, it’s the same story.

01:04:13 [Speaker Changed] It’s the same. It’s the same story. But I am a big podcast listener, so that’s the longer form way, including masters in business. Well, thank you that I absorb information beyond the traditional drivers that come into my inbox. Literally.

01:04:30 [Speaker Changed] It’s easy when you’re traveling, if you’re on a plane or a car. I just find it so easy. Yeah. Alright, so you told us what you’re, what po what other podcasts are you listening to? What are you watching on Hulu and Netflix or

01:04:40 [Speaker Changed] Amazon? Well, I, I listen to Masters in business. I love Grant Williams series of podcasts. I love ’em because they’re long form and they’re big picture and top down. My, my favorite non-inverting podcast is Smartless. I just love those

01:04:55 [Speaker Changed] Guys. Those guys are great. They’re

01:04:56 [Speaker Changed] Great. They’re, they’re so fun.

01:04:58 [Speaker Changed] I’m gonna tell you, I listened. I’ve had Michael Lewis on

the podcast at Dawson

01:05:03 [Speaker Changed] Times. I have, I have met and have interviewed Michael Lewis on stage at Schwab’s Impact Conference.

01:05:08 [Speaker Changed] And, and the story he told, and I’m not even gonna mention it, the story he told on Smartless about a family tragedy was just, it

01:05:17 [Speaker Changed] Was unbelievable. And what Right. What his friend said to him, or his therapist said to him, the reason why you’re so exhausted after this life’s tragedy is in your mind, you’re rewriting the future without, without her. Without her. Right. It’s crazy. And that was such a, a, a moment of Wow. But yeah, that was one of the most impactful interviews

01:05:36 [Speaker Changed] I’ve heard that, that I, that stayed with me for a long time

01:05:38 [Speaker Changed] In terms of what I’m watching. Well, morning Show just started back up again. Yeah. So we get back into that four four, and I loved Department Q.

01:05:46 [Speaker Changed] So did I. That was so good.

01:05:47 [Speaker Changed] It was intense.

01:05:48 [Speaker Changed] It was a little slow, but they really, it really paid off, if you like Department Q There’s a movie, I wanna say it’s on Netflix called Black Bag. That’s the same I’ve heard about it. Same sort of I’ve heard about it. Espionage thing. Yes. Yeah. And I walked in on my wife watching Killing Eve.

01:06:10 [Speaker Changed] That was great.

01:06:11 [Speaker Changed] Which she’s like, told it was great. Like, I’m like, oh, 01:06:14 [Speaker Changed] This is Queen Gambit was great.

01:06:15 [Speaker Changed] There’s, there’s been a ton of stuff. Yeah. We, we just finished the Gilded Age, which is

01:06:19 [Speaker Changed] Oh yeah. Which, that’s

01:06:20 [Speaker Changed] Feels modern.

01:06:22 [Speaker Changed] I’m obsessed with that era in New York City. Oh really? I have every book written about it. I’m just so, so that is so right up my alley.

01:06:30 [Speaker Changed] So we watched The Crown, but we never watched Doubt Abbey. And people said, oh, loved it. Loved it. Oh, you like Gilded Age in the Crown. Doubt Abbey is, absolutely. So that’s on my, and during the Pandemic, I had never seen a single episode of Mad Men. And that was mind blowing to watch that. Yeah, that’s a good one. That felt like more like a documentary. Yeah. It’s fun

01:06:48 [Speaker Changed] To go back and watch some of the old

01:06:49 [Speaker Changed] Shows. Yeah, absolutely. All right, our last two questions. Okay. We’ll get you outta here on time. A recent college grad is interested in the career in investing or doing market strategy. What sort of adv advice would you give them?

01:07:01 [Speaker Changed] Well, the world you live in and indirectly I live in on the advisor side, that’s an incredible growth area in the broader realm of financial services, independent RIAs, wealth management firms, even the wealth management divisions at the big wirehouse firms because it’s essentially a first generation business. And so there’s a lot of succession planning happening right now. And I, I think for young investors, that’s such a great avenue to go in more generic advice that I give young people, especially as they embark on the networking and interview part of the process is be way more focused on being interested than being interesting. Hmm. Don’t go in there and say, here’s all the fabulous things have I done? Especially if it’s, that’s limited to an undergraduate education, but be interested, ask questions, be engaged, show the enthusiasm. That way you’re not bringing something into the mix by virtue of what you know, econ, you know, 2 0 8 course you took that they think, oh God, we have to hire this person. ’cause we don’t know anything about that. So we’re bringing it’s is be interested.

01:08:06 [Speaker Changed] Huh. Really interesting. And our final question. What do you know about the world of investing today? You wish you knew back in the 1980s when, when you were first getting started?

01:08:17 [Speaker Changed] It, it seemed to be a little bit easier to analyze markets in that day using kind of traditional stuff. Models to think now about how much more of an influence there is of geopolitics and macro and how much more complicated an ecosystem. Not to mention the channels of information that occur through social media. I, I kind of wish it was back to what at the time didn’t feel terribly simple, but I think then was a little bit more simple and more concrete in terms of what drives markets. I think there’s more psychology now with a wider band of what that means and what that represents. And it would’ve been interesting to kind of know that in advance the little birdie landing on your shoulder saying here, here’s what, here’s what I don’t know. If I would’ve believed that 40 years from that point, I’d still be doing this, but just how much more complex an ecosystem that the markets live in these days. Huh.

01:09:19 [Speaker Changed] Really interesting. Lizanne, as always delightful. Thank you so much for being

01:09:23 [Speaker Changed] So generous

01:09:24 [Speaker Changed] With your time. My pleasure. Always really, really interesting. We have been speaking with Liz Ann Saunders. She is the Chief investment strategist at Schwab, helping to oversee $11 trillion in client funds. If you enjoy this conversation, well check out any of the 564 we’ve done over the past 11 and a half years. You can find those at YouTube, Spotify, Bloomberg, iTunes, wherever you get your favorite podcasts. Be sure to check out my new book, how Not to Invest the ideas, numbers, and Behavior that Destroy Wealth and how to avoid them at your favorite bookstore. Now, I would be remiss if I did not thank the Crack staff that helps put these conversations together each week. Alexis Noriega is my video producer, Anna Luke is the podcast producer. Sage Bauman is the head of podcasts here at Bloomberg. Sean Russo is my researcher. I’m Barry Ltz. You’ve been listening to Masters in Business on Bloomberg Radio.

~~~